This is part 2 in our follow-up series on the first centuries in Church History. We’re concentrating on the persecution Jesus’ followers endured. In part 1, we examined the social & civic reasons for persecution in the Roman Empire.

The suspicion of nefarious intent by Christians, fueled by their withdrawal from society due to its tacit connection to paganism, morphed into a suspicion of covert actions Jesus’ followers were taking to subvert society. Why were Christians so secretive if they weren’t in fact doing something wrong? And if the rumors were true, Christians WERE doing odd things; like pretending slaves had the same dignity as freemen; that women and children were to be honored as equal to men; and they rescued exposed infants. Why, if they kept all that up, and more joined their cause, what was to become of the world? It would look very different from the one that had been.

Another concern was the reaction of the gods. What would they do if the Christians had their way and everyone came to faith in a single deity? Those gods and goddesses, responsible as they were for things like weather and fertility, might throw one of their classic hissy-fits and call up a drought, a storm, or war.

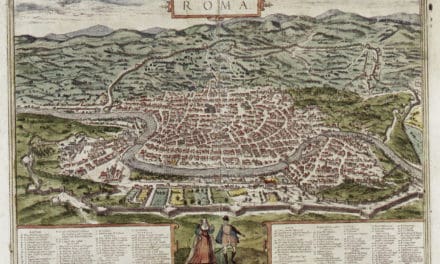

All this helps explain the 1st official wave of persecution at Roman hands. In AD 64, during Nero’s reign, fire leveled whole neighborhoods in Rome. This was neither the 1st nor last fire to devastated the City. But it was one of the most severe. For days it raged leaving a large part of the heart of Rome in ash. A rumor pointed the finger at Nero as the cause of the fire. It was well known that he planned a grand re-modelling of the City. What matter if his plans were hindered by several thousands homes. Seeing the fiction that as Emperor, he could do as he please beginning to crumble in the face of a quickly rising public rage, Nero searched for a scapegoat. He found a ready one in a group that was already under suspicion. Convenient that they held some belief in the end of the world by fire.

Large numbers of Christians were arrested. Then crucifixions began. When that got boring, they were sewn inside skins of cattle and torn apart by vicious dogs. Women were tied to bulls and dragged to death. One report says at night, Nero tied Christians to stakes in his garden, doused them with pitch, then lit them ablaze while he rode among them in his chariot.

Most likely, it’s during this persecution the apostles Paul & Peter were martyred in Rome.

This first wave of official persecution was uncommon for the 1st & 2nd Cs, but it did presage what was to come later. For long periods Christians enjoyed a measure of peace. But they knew persecution could break out at any moment. All it took was some influential person taking umbrage & the arrests started up again. Because being a Christian was technically illegal.

Things remained relatively quiet until the early 2nd C. Then a question began to rise over whether or not Rome ought to take a firmer hand in dealing with the Christians. After all, no one could ignore that fact that they were growing in numbers. Especially concerning was the number of soldiers converting to the new faith. What effect would their religion have on their fitness to serve in the legions?

As I shared in Season 1, in ad 112 Pliny, a governor in Asia Minor, wrote his friend the Emperor Trajan, asking advice in how to deal with followers of Christ. He was sure Christians were guilty of something. He just wasn’t sure what. He put no stock whatever in the wild rumors they were incestuous or cannibals.

He wrote, “I do not know just what to do with the Christians, for I have never been present at one of their trials. Is just being a Christian enough to punish, or must something bad actually have been done? What I have done, in the case of those who admitted they were Christians, was to order them sent to Rome, if citizens; if not, to have them killed. I was sure they deserved to be punished because they were so stubborn.”

What stubbornness did Pliny mean? HOW did these early Christians exhibit such stubbornness. What was it they were being required to do they couldn’t?

That arose from their failure to laud the Emperor’s genius – as it was called. The main cause of Rome’s persecution of Jesus’ followers came about from the tradition of emperor worship. The contest between Christ & Caesar didn’t happen overnight. It rose gradually because the PRACTICE of emperor worship rose gradually to attain a central place in the life of the Empire.

The roots of emperor worship lay in how Romans viewed the benefit of their hegemony. When & where they took over, a mostly impartial justice arrived. People were freed from the caprice of fickle tyrants. Roads were cleared of bandits, the seas of pirates. A superior security came to most regions. This came to be called Pax Romana, the Roman peace. But it was a peace enforced by a very sharp and deadly sword.

Many regions held a profound gratitude to Rome for disposing of their previous rulers & replacing them with, if not out-right benevolent governors, at least their avarice was restrained. Because they already believed in a host of deities, it was easy to make one more – Roma, goddess of Rome. By the 2nd C BC there were dozens of temples in Asia Minor to her. But humans like symbols, something they can see. So it wasn’t long before the spirit of Rome was regarded as imbuing the Empire’s leader – the Emperor. He was Rome. The first temple built to the godhead of the emperor was built in 29 bc at Pergamum in Asia Minor.

At first Roman emperors hesitated to accept this reverence. In the mid-1st C, Claudius refused to allow temples to be erected to him because of the ostentatiousness they suggested. But the idea grew began to grow and became attractive to later emperors.

The logic was that the Empire needed something to unite its far-flung provinces in a single, uniform practice. A kind of Pledge of Allegiance. Since nothing has the potential to unite like a common religion; Caesar-worship seemed a ready tool to forge loyalty. There was just no chance any of the disparate religions of the various regions of the Empire would be accepted by all, why not rally under the one things they’d all embraced – the political yoke of Rome. So emperor-worship became a centerpiece of imperial policy. It was officially organized in every province. Everywhere temples to the Emperor appeared.

BUT – if loyalty to Rome was announced by worshipping the Emperor, what did a refusal to worship him mean? Logic seemed to leave a single answer – Treason! So Christians who refused to offer a pinch of incense while saying “Caesar is Lord” were branded as dangerous traitors. Subversives whose presence couldn’t just be overlooked, for surely the gods were watching and required those who defied them to be punished.

During the reign of the Emperor Decius in the mid 3rd C, Caesar worship was made universal & compulsory for everyone in the Empire with the single exception of the Jews. On a set day each year everyone had to come to the Temple of Caesar & burn a pinch of incense while saying: “Caesar is Lord.” He was then given a libelli, a certificate to guarantee he’d taken the oath and sworn by the Emperor’s genius. He could then go and worship any god he liked, so long as the worship didn’t affect public decency and order.

Caesar worship was mainly a political loyalty test; a way to register someone as a “good citizen” at least as Rome defined it. But of course, it proved nothing about a person’s real loyalty. Christians, who COULDN’T participate in Caesar-worship were in fact, often better citizens than those who took the oath. Because their Holy Writings enjoined them to pray for those in authority.

Roman coins from that time have text given in adulation by Romans to the emperor remarkably similar to the praise Christians offered Christ. These coins, say things like, “Hail, Lord of the Earth, Invincible, Power, Glory, Honor, Blessed, Great, Worthy art Thou to inherit the kingdom.” That sounds an awful lot like praise directed to Jesus in Revelation.

The Worship of Christ & Caesar butted heads. No pious Christian would ever say was: “Caesar is Lord.” Jesus alone was Lord. But to most Romans, Christians seemed stupidly intolerant. Just go along to get along for goodness sake!

“For goodness sake; if there really is only 1 God as you Christians claim, then what harm is there in burning a pinch of incense & mouthing empty words. It’ll at least remove the suspicious & hostile eye of Rome from you!”

While an imminently practical idea to many Romans, it was unthinkable to most Christians. Although some in fact DID use this as justification for obtaining a libelli.

But most Christians saw it more like this: Saying Caesar is Lord was spiritual adultery; it was cheating on Jesus. Burning incense and taking the oath would be like cheating on your spouse, and justifying by saying there was no love involved; it was just sex.

è That dog’s just not gonna’ hunt!

Something for us to ponder is how this contest between Caesar and Christ which began near the start of the Church will, according to a Futurist interpretation, come round again at the end. In the Book of Revelation, John presents a major struggle between the forces of heaven and hell with Earth being the battlefield. It’s a contest of kingdoms; God’s and the devil’s, with satan’s merging with a political empire intent on wiping out believers. Historicists see that as having been fulfilled in the early centuries of the church. Futurists see it as something yet future, a recapitulation of what’s already happened but on a much wider scale.

The earliest phase of official persecution of the Church ran from about AD 64 to 100.

As already mentioned, it was touched off by the fire at Rome. The fire began July 19, 64 and lasted for 9 days. It destroyed 10 of Rome’s 14 districts and created massive suffering for the City’s million inhabitants. To divert attention from himself as the likely cause of the fire, the Emperor Nero blamed the Christians who were already suspect due to their secretiveness; and the report that they claimed the world would end in fire. If they wanted to end in fire, Nero was happy to oblige and used them as living torches in the gardens near his circus in the Vaticanus district. Both Peter and Paul were executed during this wave of persecution.

The Neronian persecution, as it’s come to be called, is notable in that it set a precedent for why the followers of Jesus were to be persecuted. Though the program of persecution didn’t really extend beyond Rome, Christians IN the City were subject to arrest and execution on the charge they were arsonists; fire being dread in Rome due to the its tendency to spread so rapidly form one house to the next.

After the first flurry of arrests and executions in the mid to late 60’s persecution diminished for some years, only to flare up again in 95, during Domitian’s reign. But this wave of hardship didn’t begin with Christians; it began with Jews, whom at that point Christians were still regarded as a reform movement of. Jews refused to pay a new tax levied to fund construction of Jupiter’s temple on the Capitoline Hill. Domitian decided to use this break with the obstinate Jews to enforce emperor worship. When they refused to take the oath, Christians were arrested for treason. Those arrested lost their property, many were banished, and others were executed; especially leaders. It was at this time the Apostle John was exiled to the prison-island of Patmos. Legend says John had been arrested by zealous officials hopeful to ingratiate themselves with the Emperor. They thought to execute John by boiling him in oil; sure to terrorize other would-be Christians leaders into submission. But God miraculously turned the experienced into a day at the spa. John came out with not hint of distress. Then fearful of whatever deity had preserved him John was bundled up and packed off to the one place he could do the least amount of damage – on a lonely prison-island in the middle of the Med. At least there his influence will be negated, right? Well, good luck with that plan you all-wise officials! It was on Patmos John received the visions that became Revelation, and which provided courage and succor to millions of persecuted believers ever since.

It wasn’t really till the early 2nd C that Rome established a policy for dealing with Christians.

A lawyer named Pliny, known to history as the Younger, because his famous uncle was known as Pliny, can you guess – yep, the Elder. The uncle was a famous author & philosopher. The Younger Pliny was as governor in northern Asia Minor from 111–13. Something of a revival must have taken place during his term as governor because there was a massive defection from paganism swelling the ranks of the Christians. Pliny was of a mind that to be a good Roman meant to hold that civic virtue we looked at last time – pietas; which meant adhering to the paganism still an official part of the Roman cultus. So many people forsaking the old gods was surely bad for the Empire. So Pliny gave anyone accused of, or who claimed to be a Christians 3 chances to recant; each time with increasing threats of punishment if they refused. If they resisted recantation after 3 warnings, they were executed.

But Pliny was unsure of this treatment accurately reflected the wishes of the one to whom he owed his office as governor – the Emperor Trajan. He wrote the Emperor asking for advice. Trajan responded that Pliny wasn’t to make it a policy to go on a search & destroy mission for Jesus’ followers. But if & when they happened to be brought to him, having been convicted of being a Christians, they were to be punished, some by torture to encourage recantation, the obstinate were executed. Trajan added that anonymous charges weren’t to be entertained; the accuser had to face the accused. This is the first real evidence we have of an official policy regarding Christians. It wasn’t long until officials across the Empire used Trajan’s guidelines in dealing with Christians. Many were martyred, including the Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, who in 115 was thrown to beasts in the arena at Rome.

Trajan’s successor, Hadrian generally continued Trajan’s policy from 117 to 138. I say generally, because Hadrian didn’t send out letters telling local officials to stay on task in regard to Christians. Some governors hated the new sect and used their official cover to persecute them. Most governors didn’t really care. Christians weren’t causing any troubles – so why kick a hornet’s nest? They left believers alone. But if suddenly there was a leanness in the ranks of fighters for the arena, well, they could always crank up another round of persecution, snag some Christians as fodder for the arena. And besides, the Church was getting pretty big – time to trim the hedge.

Occasionally at heathen festivals the mob would drink too much and want some entertainment, so they’d demand the blood of Christians. This became so common, Hadrian published an edict against such riots. Christians couldn’t’; just be roused by the mob out of their homes or meeting places & carried off to some temple or arena where their heads were used to crack rocks. No, Christians were to be given the justice of the courts. They could be executed for being Christians, but only after being properly charged and tried. During Hadrian’s reign, this policy saw the ranks of Christians grow, their wealth improve, their scholarship advance & their influence spread.

From 139-161, the Emperor Antoninus Pius appears to have personally favored Jesus’ followers. But officially he continued the precedent of imperial policy. What that means is, little direction was coming from Rome about how Christians were to be handled. Persecution at this time was sporadic, regional, and temporary. It might flare up for a few months with mobs rioting and demanding Christian blood, then several years would go by with nary a whisper of threat. A student of the Apostle John, Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, was martyred in this way; when a mob rioted and demanded some Christians pay for their defiance of the old ways and gods.

Let’s call this period, the time of provincial persecution.

We’ll end this episode here, and pick it up at this point next time as we continue to track persecution in the First Centuries.