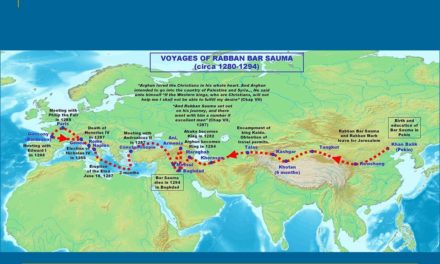

This is the 11th episode in the story of Rabban Sauma, and we’re closing in on the conclusion.

After a month-long tour of the holy sites in and around Paris, Sauma had a final audience with King Philip. He meant it to be the crowning achievement in the royal treatment he’d lavished on the Chinese ambassador.

It was held in the upper chapel of Saint-Chapelle where the just completed stained glass windows filled the room with light, giving the room its nick-name – The Jewel Box. Being newly installed, the colors were vibrant. The windows tell a Biblical history of the world. The room also holds statues of the 12 Apostles and vivid paintings that all combine to literally dazzle the eye. But it was the relics the room held that would have most impressed the Rabban. Philip carefully opened an ornate box holding, what was reputed to be, Jesus’ crown of thorns. Another reliquary held a piece of wood from the cross.

While several of Paris’ relics were indeed brought back from the Holy Land after the first Crusade, these two had been secured by Philip’s grandfather St. Louis in Constantinople 40 yrs before. Saint-Chapelle was built as simply a large reliquary to hold their reliquaries.

Sauma’s account of viewing these precious relics reports the King told him they’d been secured during the First Crusade IN Jerusalem. Either Sauma misunderstood, or Philip intentionally misled him. Philip wanted to encourage the Rabban in his appeal for a new Crusade. It’s likely Philip fudged the facts so as to give Sauma the impression the French greatly honored the idea of a campaign to retake the Holy Land, even though he had no intention of making an imminent call for one. His behavior throughout the Rabban’s visit suggests he wanted to curry the favor of the Mongol Ilkhans. Furthering that impression was the envoy and letter he sent with Sauma when he eventually returned to Persia. Before leaving Paris. Philip loaded him with lavish gifts, which the pious and humble monk lumps under the heading, “lavish gifts” in his account.

So, armed by the assumption he’d secured the French King’s commitment to a Crusade in alliance with the Mongols in Persia against the Muslim Mamluks, Sauma headed west to see if he could recruit the English King Edward I. It was fortunate that Edward just so happened to be near at hand, visiting his lands in Gascony, a region on the west coast of France just north of Spain. After a 3 week journey, Sauma arrived in Bordeaux in the Fall of 1287.

Whereas the Parisians had plenty warning of the arrival of the Far Eastern Ambassador from the exotic Mongols and went all out in their celebration of greeting, the people of Bordeaux were surprised. “Who are you and why are you here,” they asked? When word was brought to King Edward, he sought to make amends for the poor way such an august figure had been greeted. Sauma smoothed over the rough start to his embassy among the English by giving Edward the gifts Ilkhan Arghun sent and letters of greeting from he and the Nestorian Catholicus Mar Yaballaha. Edward received them with marked appreciation, but it was when Rabban Sauma proposed an alliance with the Mongols against the Mamluks that he became most animated. “A new Crusade to liberate Jerusalem and bring aid to the beleaguered Outremer? Why that sounds stellar!” was his enthusiastic reaction. Only 6 months earlier, he’d vowed to take the cross. This seemed a glow of divine favor on his pledge, an affirmation of God’s delight in him.

While Edward intended to immediately embark on the adventure, events back home conspired to stall that plan. Wales rebelled, again; and entanglements on the Continent in the fractious politics and schemes of Europe hijacked his resources and attention.

But all of that was yet future; near future to be sure, but not yet. As far as Sauma was concerned, he had the support of both the Kings of England and France in the proposed alliance with the Mongol Ilkhans in Persia in their long desire to rout the Mamluks from the Middle East.

Furthering Sauma’s sense of favor by the English King was the invitation to officiate Communion for the royal court. Though Sauma consecrated and served the elements according to the ancient Syriac formula, it was enough akin to the Mass that the participants were easily able to follow along, understanding not the words, but the meaning behind each movement of the ritual.

And THAT – is simply remarkable!! Think of it. Though it’s the close of the 13th C, and these two branches of The Church have been sundered from each other for 800 yrs, when adherents from the two groups engage in the focal point of their religious service, though they can’t understand one another’s speech, they DO understand what’s happening, because the rite itself hasn’t fundamentally changed. That’s stunning, by anyone’s reckoning.

Once the service was finished, Edward threw a feast. It was his way to finalize and seal the agreement between England and Persia. Sauma didn’t record what this royal feast served, but we have accounts of some of Edwards’ other such feast. Let me just pass along the idea that you can go right ahead and picture the most raucous dining hall scene from any medieval movie with the ox spinning on a spit over a huge fire, chicken bones being thrown across the room in mass quantities, platers laden high with all kinds of bread and vegetables. And keg after keg of drink. Edward was known for these kinds of food & beverage extravaganzas.

And once again, having achieved his official duties as Arghun’s ambassador, Sauma turned to his personal mission; visiting the holy sites of Edwards’ domains on the Continent. Edward not only provided guides, he paid all Sauma’s expenses for this pilgrimage.

When he returned, Edward did something curious. He took pains to make sure Sauma understood that European Christians believed in Christ alone. It seems someone may have gotten to the King and informed him of the ancient rift between the Nestorian and Western Church. For his part, Sauma wasn’t going to throw over the much-needed alliance between East and West over nuances of theological wording that people who 800 years earlier had divided over – and THEY spoke the same language. A lengthy dissertation on the nature of the Trinity through translators just wasn’t practical. So Sauma let it go.

Late in 1287, with two-thirds of his mission accomplished, The Rabban decided it was time to head back to Rome and see if a new Pope had been selected. Two of Europe’s most powerful armies were now committed to the cause. All they needed was permission from Rome’s Bishop. By the end of the year, the obstinate cardinals still had not made a selection.

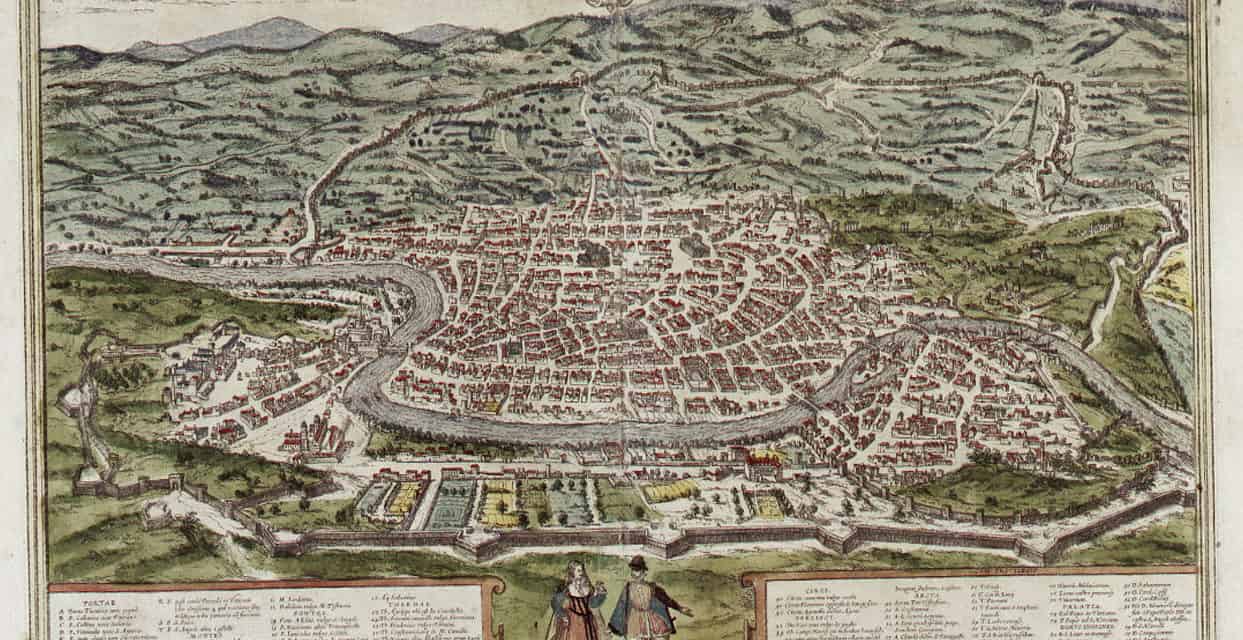

Fleeing the cold of the French winter, he traveled to Genoa to await the election of the New Pope. Sauma’s report of Genoa makes it clear it was maybe his favorite place in all his travels. The city was a beauty, the people warm and friendly.

As much as he loved Genoa, Sauma’s sense of responsibility began needling him. He wasn’t, as they say, getting any younger. The trip back to Persia with his report to Arghun was going to be another major epic in a life FILLED with them. If the last months’ long journey from Persia to the West had aged him years, the return trip would age the now sexagenarian a decade. He couldn’t return to Persia by hopping aboard a 747. It meant another rickety ship across some of the most dangerous waters of the Med, to Constantinople, then across the Black Sea with its plethora of pirates, to the western end of the Silk Roads, then across Mesopotamia to Persia. [And we complain when we need to hop in the car and drive to the market down the street!]

It’s not difficult sympathizing with Sauma’s rising guilt at enjoying Genoa when he knew how eager both his friend Mar Yaballaha and his ruler, Ilkhan Arghun was for his return and report. Sauma was a man with a profound sense of duty. What else could account for the multitude of manifest difficulties he’d endured over the previous decade? But Genoa had everything he’d been looking for in his pilgrimage. Duty won out over ease and Sauma began to chaff as he waited for the Cardinals in Rome to get it together.

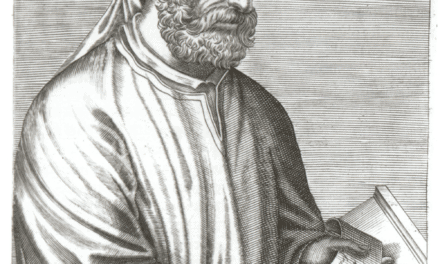

They finally did. In February 1288 they elected Jerome of Ascoli as Pope Nicholas IV. It was an auspicious choice for Sauma’s mission. Some years before, Jerome had been Rome’s ambassador to Constantinople to see about effecting a reconciliation between East & West. The effort proved unfruitful, but it made Jerome more aware of the needs and sensitives of the Eastern Church. If any Europeans can be said to be aware of the threat the Mamluks presented the Faith, Pope Nicholas IV was among them.

It helped Sauma’s cause that Nicholas was one of the people he’d spent considerable time conversing with when he’d before been in Rome. The two had hit it off, despite the language barrier.

Nicholas sent an envoy to Genoa requesting Sauma’s return to the Eternal City. Two weeks later, as Sauma’s party reached Rome’s outskirts, they were met by a delegation of church officials welcoming him to the City.

Ushered into Nicholas’ presence, Sauma showed him the highest form of obeisance he could by bowing on hands and knees, kissing the Pope’s hands and feet, then rising to walk backward with arms crossed at the wrists before his chest; a Nestorian sign of the utmost honor. Sauma then delivered the last of his official letters and gifts from Arghun and Mar Yaballaha.

Nicholas showed his ready acceptance of Sauma’s embassy and person by requesting he stay and celebrate Easter with his Western brethren. Nicholas knew that Sauma, as a Nestorian Rabban, would feel the need to officiate at the events of Holy Week in some church setting. So rather than travel, we suggested he stay and plan on doing so there in Rome. Plush lodgings were secured for him and his attendants.

Sauma then began preparations for Easter celebrations. He requested permission to conduct Mass so as to show Western Christians how it was done in the Nestorian tradition. The pope not only granted him permission, he showed great curiosity to witness the ritual. When the time came, a huge crowd was on hand. When all was said and done, the consensus was the same as in Bordeaux. While the language was different, the ritual was so similar as to make the differences inconsequential. So interesting was Sauma’s conduct at the Mass, the Pope invited him to officiate at more services over the next few weeks. The Rabban asked in return of the Pope would favor him by serving him the Eucharist, which Nicholas heartily assented to. The day was Palm Sunday of 1288.

Sauma reports that the crowds attending service that day were beyond anything his imagination could have conjured. People literally filled the streets, carrying branches of palms and olives.

On Maunday Thursday of the next week, so many people packed the church where the Pope held Mass that when they said a united “Amen” the walls shook. The service over, the Pope then made the rounds of several locations in Rome where he bestowed blessing and favor on various people and artifacts. He ended by bringing his entire household staff together and washing their feet. Sauma was hugely impressed with this act of papal humility, describing it in depth. The day ended with a huge feast for some 2000.

Good Friday began with a procession from the Church of the Holy Cross, where the Pope held aloft a piece of the Cross as massive crowds once again attended the scene. The rest of the day was spent in quiet meditation on the sacrifice of Christ.

Saturday saw the Pope making the rounds to bestow more blessing on individual shrines and folk. Then Easter Sunday services were conducted in the ancient Church of Saint Maria Maggiore.

Sauma knew his fellow Nestorians were curious about the practices of their Western Cousins, so he paid close attention to all that was happening around him., recording the events in as intimate detail as he could.

Easter being complete and his mission now finished, Sauma asked permission to return home. Nicholas asked him to stay. Sauma struck for compromise He was more than pleased to stay, especially since it came from a sincere request on the part of the Pope with whom he was getting along well. BUT, a higher purpose was to be served in his return to Persia where he could share with the Mongol ruler the favorable reception he’d been shown across Europe. Certainly, that had to be a good harbinger of a future alliance. When word got out about the success of Sauma’s mission, lingering tensions between East & West would subside. Such was the nature of medieval diplomacy.

Then Sauma made a request that threatened to blow everything up.

Picture that scene in a movie where two parties who are potential enemies, are in fact getting along and everyone’s on pins and needles hoping for a new day of peace. Then there’s a pause, and one of them says something that threatens to ruin it all. But the representative of the other aide at first just stares at them with a look of, well. That’s the problem; no one knows what to think. And everyone starts moving their hand slowly toward their gun because they think, “Oh no. This is it. Get ready to start shooting.” But then the guy breaks out in a huge smile and starts laughing. The tension is immediately released.

That’s the scene when Sauma asked the Pope, for … Ready? è Some sacred relics. At first, Nicholas was stunned at the boldness of Sauma’s request. Nay; it was more than bold; it was brazen. He told the Rabban that if he were in the habit of giving relics to every foreign emissary who came to see him, there’d soon be nothing left in Rome to give.

Still, in light of Sauma’s perilous and long journey, he was pleased to give Sauma some treasures to take home. He gave him some scraps of cloth from clothes that were said to have belonged to Jesus and Mary, as well as various relics of different saints and special vestments for Mar Yaballaha. Maybe the most significant gift Nicholas bestowed was a letter patent authorizing Mar Yaballaha and his Nestorian Catholicus successors as the authority over the Church of the East. He gave Rabban Sauma a letter patent naming him Visitor General for all churches of the East, not just China, as the previous Nestorian Patriarch had done.

Implied in Nicholas’ issuing of these letter-patents was that HE, as the Roman Pope, had jurisdiction over the East. Sauma might like to have contested that. But what point? It’s not like he was going to get Nicholas to back down. For goodness sake, the question of prime ecclesiastical authority had been going on for hundreds of years. Sauma was under no illusion he was going to set things right now. Rather, all he could do was blow up the alliance that seemed to be a done deal.

After giving Sauma a large gift of gold to help pay his expenses, Sauma began preparations to return home.

Nicholas gave Sauma a letter for Arghun, thanking the Mongol ruler for his beneficent rule of the Christians of his realm and thanking him for his offer of an alliance against the Mamluks. A copy resides in the Vatican museum. Then Nicholas launched into an appeal for both Mongols and Nestorians to submit to papal authority. He urged Arghun to convert to Christianity post haste and be baptized under the authority of Rome.

Then he indicated while Sauma had indeed faithfully transmitted the Ilkhan’s desire for an alliance, he and he alone could call a Crusade. The secular rulers of Europe might be gung-ho but they had no authority to approve a Crusade. Only he, as the head of the Church, possessed that right. AND, knowing the mindset of the rest of Europe, besides the monarchs of England and France, a Crusade wasn’t in the cards at that time. So he adroitly side-stepped making a commitment, while at the same time, encouraging the Mongols to do their best against the common enemy.

Arghun had indicated a willingness in his letter to the Pope to convert and be baptized IF that baptism could be done in a reclaimed Jerusalem, one free of the Mamluk scourge. Nicholas said Arghun had it backward. He ought to convert and be baptized NOW. That would assure him of heaven’s favor in any campaign he undertook. His example would surely lead to mass conversions, furthering the promise of divine favor.

So the Pope didn’t out-right turn down an alliance not forbid a Crusade. He just shifted the emphasis of his letter onto the need for Arghun to trust God and surrender to him, which of course would be done by accepting the Roman Church’s hegemony over his realm.

Nicholas wasn’t done with his letter writing. He penned one to Mar Yaballaha as well. This one began by praising the Nestorian Catholicus for his wise leadership of a challenged Church. But then it went into a long lecture on “proper” Christian doctrine, something the Nestorian Patriarch wasn’t at all likely to look kindly on. The last paragraph was a blatant and tactless statement of the supremacy of the Roman church.

Since these letters were open, Sauma read them both. He was deeply disappointed at the tone they took with the two men he reported to. Their condescending tone was sure to dishearten and alienate their recipients. The Pope refusal to sanction a Crusade or give any support to the proposed alliance seemed to make his entire trip West pointless.

No doubt disappointed, Sauma managed to tamp down any expression of it in his concluding meeting with the Pope. He was probably just glad to be quitting the West & the prospect of going home.

We’ll wrap up Bar Sauma’s magnificent tale in our next episode.