This episode is titled – Popes.

We begin with a quote from Pope Leo I and his Sermon 5 …

It is true that all bishops taken singly preside each with his proper solicitude over his own flock, and know that they will have to give account for the sheep committed to them. To us [that is: the Popes], however, is committed the common care of all; and no single bishop’s administration is other than a part of our task.

The history of the Popes, AKA the bishops of Rome, could easily constitute its own study & podcast. Low & behold there IS a podcast by Stephen Guerra on this very subject. You can access it via iTunes or the History podcasters website.

Our treatment here will be far more summary & brief, in keeping with our usual method.

Several of the factors that elevated the Church at Rome to prominence by AD 200 were still pertinent to in the 4th & 5th Cs. Theologically, while at the dawn of the 3rd C Rome claimed an over-riding apostolic authority derived from both Peter & Paul, by the 5th Paul was dropped. His historical role in the Church at Rome was forgotten in favor of the textual argument based on 3 key NT passages that seemed to assign Peter a special place as de factor leader of the church under Christ. For those taking notes, the passages were Matt 16, Luke 22, & John 21.

As noted in previous episodes, another factor lending weight to Rome’s claim as premier church was the steadfastness of the bishops of Rome during the Arian controversy. Rome simply maintained a reputation for orthodoxy. It’s interesting that the bishops of Rome never attended an ecumenical council. By doing so they ostensibly avoided the political maneuvers that often accompanied the councils; as we saw with Cyril & Nestorius, & the nasty schemes that embroiled the churches of Alexandria & Antioch.

Administratively, Rome adhered to the tradition of a local & provincial synod twice a year. This group of conservative bishops was the vehicle through which their leader, the bishop of Rome, acted. This stood in stark contrast to the synod at Constantinople, held only when some need pressed & attended only by those bishops inclined to show up. And when they did, the bishops held varying loyalties between Alexandria, Antioch, & Constantinople. You remember the Robber’s Council at Ephesus where it became a bloody brawl. And the Eastern Councils even altered each other’s creeds & conclusions. With this kind of confusion in the East, it’s little wonder Rome appeared a bastion of stability.

Geographically, by reason of his location, the Roman bishop had a voice that was heard far & wide. Keep in mind that, Rome was the only patriarchate in the West.

Politically, Rome, while still highly symbolic, was no longer the political center of the West. Milan, then later Ravenna were the capitals of the Western Empire. With the royal absence, Rome’s bishop became the city’s most important figure. Likely for this reason alone, the associations of imperial Rome began to surround the church’s government.

The word ‘pope’ derives from a word used by Greek children for their father = papas. It was first used in Latin the beginning of the 3rd C as an informal title for the bishop of Carthage. From there, the bishops of Alexandria picked it up & began to be called “pope” a few decades later. It’s still the title of the Coptic patriarch of Alexandria.

The first known use of the word for the Bishop of Rome comes from an inscription in 303 for Marcellinus, [MAR-shuh-LEE-noss] but a lack of attribution going forward over the next decades means the word was not a common title till much later in the 4th C. The title then became almost exclusively associated in the West with Roman bishop from the 6th C on.

In covering how the Bishop at Rome BECAME the Pope, we need to look at HOW it was that the other bishops came to regard him, not just as first among equals, but as someone ordained by God to be in authority over them; someone they owed obedience to as God’s Earthly representative. It’s evident to anyone who takes the time to study the subject that while a growing number of bishops came to this conclusion, it was by no means something everyone acknowledged. The issue even led to the great rift between the Eastern & Western churches. // So Let’s track, in outline at least, how the bishop at Rome became Pope.

In the mid-4th C, during the tenure of the Roman bishop Julius, the 3rd canon of the Council at Sardica in 343 established the rule that a bishop who’d been deposed could appeal to the bishop of Rome. This was an important step in the recognition of his appellate authority.

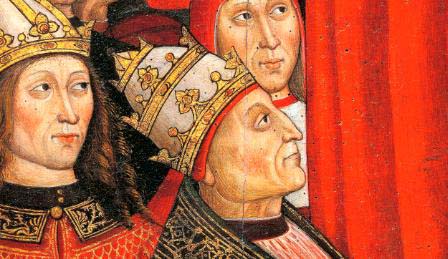

In the mid 4th C, the most important bishop of Rome for advancing the claims of his see was Damasus [Dah-MAH-sus]. He became bishop after a contested election in which there was bloodshed between his supporters and those of his rival Ursinus [ur-ZEE-noos]. Damasus made regular references to Rome as “the apostolic see” & spoke of the “primacy of the Roman see” on the basis of Matthew 16:18. Damasus sanctified the burial sites of previous Roman bishops in the catacombs, marking them with ornate inscriptions, he reformed the Latin liturgy, & commissioned Jerome to revise the Latin Bible.

Instead of adopting the posture & accoutrements of a humble shepherd of God’s flock, Damasus affected an imperial aura reminiscent of an emperor. So exalted was he that the pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus hinted he might become a Christian if he could be bishop of Rome.

At the end of the 4th C, Bishop Siricius regarded even his letters as being authoritative edicts & styled them as “apostolic.” Shortly after that, Innocent I declared that Sardica’ s 3rd canon giving the Roman Bishop appellate power was retroactive to the Council of Nicaea in 325. Innocent said the Church’s highest teaching authority belonged to Rome. He extended his authority beyond the realm of the Western Empire into the province of Illyricum and started referring to the Roman Bishop as “vicar.”

Boniface I prohibited appeals beyond Rome.

Leo I, AKA Leo the Great, can rightly be referred to as the first pope in that he embodied what that title means for most people today. He combined authority over councils & emperors with the idea the Roman Bishop was Peter’s successor in constructing his theory of the papacy.

As we saw in the episode a while back on Leo, his 3rd Sermon, delivered on the 1st anniversary of his election, explained the Petrine theory in terms of the Roman law of inheritance. Leo argued Jesus gave Peter the keys of the kingdom, so authority over the other apostles. He also claimed, after long tradition that Peter was the first bishop of Rome, and his authority was passed on to the subsequent bishops of Rome. Therefore, Leo reasoned, the perpetual authority of Peter is found in the Roman bishop. He dispensed with earlier views of church leadership & made the authority of bishops dependent on the Pope.

Since this is a Church History, not a theology or ecciesiology podcast, I’m not going to go into what I, as an Evangelical Protestant, find tenuous in Leo’s position.

What’s important for our purposes here is to realize that now, the bishop of Rome stood between Jesus Christ and other bishops.

When Leo’s Tome was read at the Council of Chalcedon, the bishops echoed his claim with the acclamation that Peter spoke through Leo. Chalcedon was unusual in that it gave assent to Rome’s teaching authority; something previously unknown and later seldom acknowledged in the East.

While Rome’s primacy was taken as fact in the West, it was a different story in the East. The Council of Chalcedon ranked the Eastern Capital as next to Rome in terms of authority. But Rome never accepted that canon, concerned that by doing so it would degrade Rome’s claim to absolute authority.

Leo drew a comparison between the 2 natures of Jesus and the 2 parts of the empire; that is, the the religious a7 the civil. Specifically, he referred to the priesthood and the kingship. He compared Peter and Paul as founders of the Roman church to Romulus and Remus as the founders of the Roman city. He presented the Pax Christianum as counterpart to the Pax Romanum.

Leo’s policy toward the barbarians was to civilize & sanctify them. They called him the “Consul of God.” Leo negotiated with the Huns Attila to get them to turn back from Rome. He even claimed the title of the pagan chief priest of Rome, the “pontifex maximus” for himself; chief bridge-builder. He was the 1st Roman bishop to be buried in St. Peter’s.

It’s clear that most of the powers & privileges of future popes were seen in Leo’s methods, & policies. He acted as a head of Rome’s civil government, checked the advance of barbarians, enforced his authority on distant bishops, preached doctrine, & intervened at Chalcedon.

While Augustine provided the intellectual substance for the medieval Western church, Leo laid down its institutional form.

At the end of the 5th C, Pope Gelasius took Leo’s papal theory even further. He foresaw that the Emperor Marcian’s claim to being a spiritual authority & kind of priest-king at the Council of Chalcedon was dangerous. Gelasisus said that the Old Testament functions of prophet, priest, and king, were filled by Jesus Christ alone as the God-Man. Among mere humans, these functions had to be kept separate. And that in the Kingdom of God, priests were superior in authority to kings. This position became a major point of tension throughout the Middle Ages. It will be the crucible that produces much of the history of Europe for the next few hundred years.

Pope Gelasius continued the claim it was the office of the Roman church to judge other churches, but could be judged by no human tribunal.

By the end of the 5th C, the Western Church virtually equated the kingdom of Christ with the Church. In the East the ideal of a Christianized empire continued on. The reign of Eastern Emperor Justinian seemed an affirmation, even a confirmation of this.

As we end this episode, I want to take a little time to try & clarify some words that anyone who studies church history is bound to encounter. It’s some titles for church leaders. The problem is sorting out exactly what these words & titles mean; WHO they refer to.

I’m referring to the words–pastor, priest, monk, bishop, archbishop, metropolitan, & patriarch.

What follows is BY NO MEANS a technical definition for these things. This is meant as a more practical and vastly simplified working definition for those who wants a quick handle on what these things mean as they review church history.

Understand right off that these are also words that have been fluid in terms of definition over time.

Pastor is a good NT word that’s synonymous in the NT with the word’s elder & bishop or overseer. All the words refer to the same office & ministry in a local church. And BTW, they do refer to that scope – a local church; not someone who oversees other pastor-elder-bishops.

Elder refers to a man’s maturity & character as morally & spiritually fit to lead a local church.

Bishop refers to his office as a spiritual authority as an overseer,

while pastor refers to his task as a shepherd of God’s flock.

A hundred or so years after the Apostles, pastors were regularly called bishops because they oversaw a team of fellow elders & deacons who served God by serving His people. We ought to think of bishops as equivalent to senior or lead pastors in today’s churches.

Now, keeping to that analogy, imagine there aren’t several dozen churches of different denominational stripes in your town; there’s just one church, led by a senior pastor bishop. That church sends out several younger pastors to plant churches in surrounding communities. They are going to look to their sending church and its bishop as a kind of spiritual parent. And if they in turn send out even more pastors to plant more works, that original sending church and pastor takes on a highly respected role of providing guidance, not just for his local congregation, but all the works they spun off. SO, he becomes archbishop – because all those local pastors are called, bishops, right?

What happened over the first few hundred years of church history was that 5 churches became recognized as canters of church life and authority, 1 in the West at Rome and 4 in the East; Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople, & a 4th that varied over time from Jerusalem, to Caesarea, & Carthage. The bishops of these 5 churches were at first affectionately referred to as patriarchs because they were regarded as spiritual fathers to their surrounding provinces. Over time, that title morphed from being merely an unofficial term of affection to an outright title, spelled CAPITAL P – Patriarch.

The title “Metropolitan” was applied to the bishops of other large cities and their surrounding provinces beyond the 5 Patriarchates. Metropolitan is essentially synonymous with arch-bishop.

A priest was someone who was officially ordained by a bishop to serve communion and baptize converts. That of course was just a very small part of his overall pastoral duties.

Monks were people who devoted themselves to the service of God rather than secular employment. They may or may not be ordained as priests. Typically, they lived alongside other monks in a cloistered community.

Again, this is a highly simplified description of these roles. But I hope it serves to help those of you doing your own reading in church history to sort out the various church offices.

Till next time …

Hello Lance.

I really appreciate the Podcase series you’ve produced here. It’s really helped me on my Christian walk so thank you. I’m having trouble downloading this episode, any ideas why?

With Christian love,

Isa

Isa,

Thanks for the kind words.

I just checked and it works fine for me.

Try again and let me know if it doesn’t work.

Lance