The title of this 48th episode of CS is “Charlemagne – Part 1.”

The political landscape of our time is dominated by the idea that nation-states are autonomous, sovereign societies in which religion at best plays a minor role. Religion may be an influence in shaping some aspects of culture, but affiliation with a religious group is voluntary and distinct from the rest of society.

What we need to understand if we’re going to be objective in our study of history is that, that idea simply did not exist in Europe during the Middle Ages.

In the 9th C, the Frank king Charles the Great, better known as Charlemagne, sought to makes Augustine’s vision of society in his magnum opus, The City of God, a reality. He merged Church and State, fusing a new political-religious alliance. His was a conscious effort to merge the Roman Catholic Church with what was left of the old Roman political house, creating a hybrid Holy Roman Empire. The product became what’s called Medieval European Christendom.

How did it come about that Jesus’ statement that His kingdom was not of this world, could be so massively reworked? Let’s find out.

300 years after the Fall of the Western Empire to the Goths, the idea and ideal of Empire continued to fire the imaginations of the people of Europe. Though the barbarians were divided into several groups and remained at constant war with each other, the longing for peace and unity that marked the region under the Roman Eagle held a powerful attraction. Many looked forward to the day when a new Empire would appear. Just as the Eastern Empire centered at Constantinople saw itself as Rome-still, the vestiges of the Western Empire along with their German neighbors hoped the Empire would (insert Star Wars reference) strike back and rise again.

By merging the Roman and Germanic religions, customs and peoples, the Franks under Clovis became the odds on favorite to accomplish what many hoped for. But Clovis’ dynasty began to fall apart not long after he passed from the scene. His descendants were at odds with each other, vying for pre-eminence. They became adept at intrigue and treachery.

The power vacuum created by their squabbles gave room for wealthy aristocrats to gain power. Like 2 dogs fighting over a scrap of food, while they’re busy snarling and snapping at each other, the cat comes and quietly steals away what they’re fighting over. So it was with Clovis’ descendants, the Merovingians. While they fought each other, the landed nobility quietly stole more and more of their authority. Among these emerging aristocrats was one who worked his way into the heart of power to become the most influential figure in the kingdom. He was called the “majordomo” or “mayor of the palace.”

The majordomo was the real power behind the throne. He ran the kingdom while the king served as little more than a ceremonial figurehead. The idea was that the son of the previous king wasn’t necessarily the one most fit to rule just because of his birth. So while the title went legally to him, the day-to-day business of running the realm was better served by another with the skills to get the job done.

In 680, Pepin II became majordomo for the Franks. He made no pretense of his desire to supplant the Merovingian line with his own as the de-facto rulers. He took the title of Duke and Prince of the Franks and made moves to ensure his line would eventually sit the throne.

His son, Charles Martel, became majordomo in 715. Charles allowed the Merovingian kings to retain their title but as little more than figureheads. What catapulted Charles to the throne was his defeat of the Muslims in 732.

In 711 a Muslim army from North Africa called the Moors invaded Spain and rolled back the weak kingdom of the Visigoths by 718. With the Iberian Peninsula under their control, the Moors began raiding across the Pyrenees into Southern Gaul. Until this time, the Muslims had advanced at a steady pace out of the Middle East, across North Africa, then into Europe. It seemed no one in the West could stop them and the fear of the infidel hordes running amuck throughout the lands of Christendom was a terror.

In 732 Charles led the Franks against a Moor raiding party near Tours, deep inside the Frank’s land. He inflicted such heavy losses the Moors retreated to Spain and were never again a major threat to Western Europe. For this and his other conquests, Charles was called Martell – “the Hammer.”

Martel’s son, Pepin III, also known as Pepin the Short, considered it time to make the power of the Frank majordomo more official. Why not give the title of “king” to the guy who was actually ruling, instead of some royal spoiled brat who thought armies were just large toys to play with? Pepin III asked Pope Zachary for a ruling saying whoever actually wielded power was the legal ruler. He got what he wanted, promptly deposed the last Merovingian King, Childeric III, and was crowned the first of the Carolingian kings by the bishop of Mainz in 751. Childeric was quietly shuffled off to a monastery where he was told to mind his manners or he’d wake up dead one day. Then, 3 years after Pepin’s coronation, Pope Stephen II himself blessed him by making the trip from Rome to Paris and personally anointing Pepin as the “Chosen of the Lord.”

Both Popes Zachary and Stephen were eager to shore up the alliance with the Franks begun with Clovis because of the emerging problem with the Lombards. They’d already conquered Ravenna, the center of Byzantine power in Italy. The Lombards demanded tribute from the pope and threatened to take Rome if it wasn’t paid. With Pepin’s coronation, the Church at Rome secured his promise of protection and his pledge to give the pope the territory of Ravenna once it was recovered. In 756, the Franks forced the Lombards to surrender several of their Italian conquests, and Pepin kept his promise to give Ravenna to the Pope. This was known as the “Donation of Pepin,” and came to be called the Papal States. This made the Pope a temporal ruler over a strip of land cutting across Italy.

This alliance between the Franks and the Church at Rome, or more properly, between the Carolingian kings and the Popes, had a dramatic impact on the course of European politics for centuries to come. It sped up the separation of the Latin and Greek Church by giving the Popes an ally to replace the Byzantines. And it created the Papal States which will play a major role in Italian politics all the way up to the late 19th C.

But one of the most significant issues was that with the Popes taking a hand in anointing kings, it set the stage for the eventual vying for power between Church and State, between Pope and Emperor. The question became: Who was really in charge? The Pope—who by reason of setting the crown on the king’s head, sanctioned his rule, or the King—whose armies were the enforcement end of the Pope’s staff and protected him from enemies? Do popes make kings, or do kings make popes? Fire up the medieval merry-go-round.

It was Pepin III’s son who took all that his father and grandfather had done and put the cap on it. His name also was Charles; Charles the Great; known to us as Charlemagne.

When Charlemagne succeeded his father in 768 he had a far-reaching vision of making Central Europe into a new Empire, similar to the Golden Age of Rome, but this time enlightened by Christianity.

To accomplish this vision he had 3 objectives:

1) Boost the Franks military might so they could dominate Europe,

2) Secure an alliance with the Church to unite Europe under one faith,

3) Make this European base an intellectual center.

Charlemagne’s success, if we can call it that, set the course for Europe for the next thousand years.

Charles the Great was a big man. At 6’3” he was a full foot taller than average at that time. But to those who met him he seemed even bigger because he was one of those people who had an extra dose of gravitas. He was skilled at arms and was always at the head of the army when they went into battle, which he led the Franks in every year.

The Merovingians had wasted the strength of the Franks in incessant civil wars. Charlemagne united the Franks and set them on the task of conquest. He took advantage of feuds among the Muslims Moors in Spain and in 778 crossed the Pyrenees in an attempt to reclaim the Iberian Peninsula. His first campaign was met with minor success but later expeditions drove the Moors back to the Ebro River and established a frontier known as the Spanish March centered at Barcelona.

Then Charlemagne conquered the Bavarians and Saxons, last of the independent Germanic tribes. He ruthlessly attempted to stamp out the residue of Germanic paganism by passing harsh laws, such as saying eating meat during Lent, cremating the dead, and pretending to be baptized, were offenses punishable by death.

The kingdom’s eastern frontier was continually threatened by Asiatic nomads related to the Huns known as the Slavs and Avars. Charlemagne decimated the Avars and set up his own military province in the Danube valley to guard against future plundering. He called this the East March, later called Austria.

Then, like his father before him, Charlemagne sought to take a hand in Italian politics. The Lombards invaded that territory Pepin had given the Church. So, in 774 at the Pope’s urging, Charlemagne once again defeated the Lombards and proclaimed himself their king.

The Lombard’s campaigns and conquests made it clear the Popes needed protection. Only one military and political power had that ability, the Frank king. Charlemagne, on the other hand, needed divine sanction to accomplish his goal of uniting Europe. Only one authority possessed the religious mojo to do that – the Pope. Can you see where this is headed?

April 25, 799 was St. Mark’s Day, a day set aside for repentance and prayer. It seemed the right thing to do since Italy had been stricken by numerous problems, including plague and pestilence. So Pope Leo III led a procession thru Rome beseeching God’s forgiveness and blessing.

The procession wound thru the middle of the city to St. Peter’s. As it turned a corner, armed men rushed at the pope. They drove off his attendants, and pulled Leo off his horse, carting him off to a monastery favorable to their cause. That being that they were officials and dignitaries loyal to the previous pope, Adrian I. Perjury and adultery were the charges leveled at Leo. The pope’s supporters tracked him down and rescued him.

This created a furor that sparked on-going riots that could not be quelled. So Pope Leo once again sent for Charlemagne. He crossed the Alps with an army, determined to settle the pope’s problem once and for all. He put down the unrest and in December presided over a large assembly of bishops, nobles, diplomats and malcontents. In other words, anyone who considered themselves someone and held a hand in the political game was in attendance. Then, the pope, wielding a Bible, took an oath swearing innocence in all charges against him. That brought the mutiny against him to an effective end. But it set the stage for a far more momentous development.

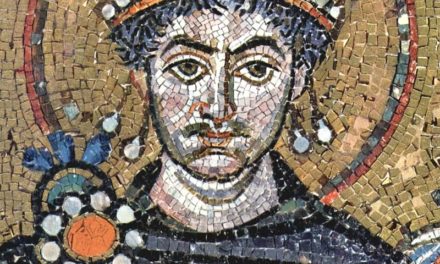

2 days later, Christmas Day AD 800, Charlemagne arrived at St. Peter’s with a large retinue for the Christmas service. Pope Leo sang the mass and the king knelt in prayer in front of Peter’s crypt. The pope approached the kneeling monarch carrying a golden crown. Leo placed it on Charlemagne’s head as the congregation cried: “To Charles, the most pious, crowned Augustus by God, to the great peace-making Emperor, long life and victory!” The pope then prostrated himself. Charlemagne, King of the Franks, had just become the first king of the Holy Roman Empire.

We’ll conclude Charlemagne’s story next time.