This episode is titled, The Ultimate Fighter; Reformation Edition.

The pioneer of Protestantism in western Switzerland was William Farel. Some pronounce it FAIR-el, but we’ll go with the more traditional Fuh–REL.

He began as an itinerate evangelist; always in motion, tireless, full of faith and fire. He was bold as Luther but more radical. He also lacked Luther’s genius.

He’s called the Elijah of the French Reformation and “the scourge of priests.”

Once a devoted Roman Catholic who studied under pro-reform professors at the University of Paris, Farel became a loyal Protestant, able only to see only what was wrong with the Catholicism of his past. He loathed the pope, branding him antichrist, as did many Protestants of the time. Of course, the popes returned the favor and labeled Reformation leaders with the same title. Farel declared that all the statues, pictures and relics found in Roman churches were heathen idols which ought be destroyed.

While Farel was never officially ordained, he thought himself divinely called, like a prophet of old, to break down idolatry and clear the way for the worship of God according to God’s Word. He was a born fighter and echoing Jesus, said he came, not to bring peace, but a sword. He contended with priests who carried firearms and clubs under their frocks, and fought them with the spiritual sword of the Scriptures. Once he was fired at, but the gun blew up. Turning to the man who’d shot at him, he said, “I’m not afraid of your shots.” He never used violence himself, except in the verbal salvos he was fond of firing at critics.

Farel was never discouraged or dissuaded by opposition. On the contrary, persecution stimulated him to even greater labor. His outward appearance gave no hint to his indomitable will: he was of short stature and looked frail. His pale complexion was oft sunburnt. His red beard was left to grow wild.

What his appearance lacked, his voice made up for. When he spoke, he used both gestures and language that commanded attention and produced conviction. His contemporaries referred to the thunder of his eloquence and of his earnest and moving prayers.

His sermons were extemporaneous but sadly weren’t preserved. Their power lay in their delivery. Farel was the George Whitefield of the 16th C.

His strength ended up a weakness. His lack of moderation and discretion unburdened him from second guessing himself, so he would speak his mind without the need to put a fine point on everything for fear of breaking a few eggs, so to speak. But his outspokenness got him into trouble again and again, not only with Roman Catholics but with his Protestant peers.

He was an iconoclast. His verbal violence provoked unnecessary opposition, and often did more harm than good. One Reformation leader of the time wrote Farel saying, “Your mission is to evangelize, not curse. Prove yourself to be an evangelist, not a tyrannical legislator. Men want to be led, not driven.” Shortly before his death, Zwingli exhorted Farel not to be so rash.

That may be a good way to see Farel’s contribution to the Reformation. His work was destructive rather than constructive. He could pull down, but not build up. He was a conqueror, not an organizer of his conquests; a man of action, not a man of letters; a preacher, not a theologian. In a large construction company, the first team that comes in is the demolition crew. They’re job is to clear away the old and prepare for the new.

Farel was a one-man demo squad; a religious wrecking-crew.

The thing is, he knew it, and handed his work over to the genius of his younger friend John Calvin. You’ll remember it was William Farel who persuaded Calvin to help out in Geneva. In the spirit of genuine humility and self-denial, he was willing to decrease that Calvin might increase. This is the finest trait in his character.

William Farel, the oldest of seven children of a noble but poor family, was born in 1489 at Gap. No, he wasn’t born in the changing room of a clothing store in the mall. Gap was a small town in the Alps of SE France, where the Waldensians once lived. He inherited the Roman Catholic faith of his parents. While still young, he made a pilgrimage with them to a supposed piece of miracle-working wood believed to be taken from the original cross. He shared in the superstitious veneration of pictures and relics, and bowed before the authority of monks and priests. He was, as he later said of that period of his life, more popish than the Pope.

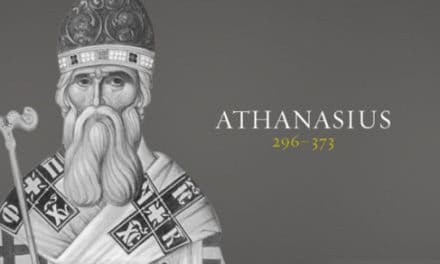

At the same time he had a great thirst for knowledge, and was sent to Paris to further his education. There he studied ancient languages, philosophy, and theology. His main teacher, was Jacques LeFèvre, pioneer of the French Reformation and translator of the Scriptures who introduced Farel to Paul’s Epistles and the doctrine of justification by faith. LeFèvre told Farel in in 1512: “My son, God will renew the world, and you will witness it.” Farel acquired a Master of Arts in 1517 and was appointed teacher at the college of Cardinal Le Moine.

The influence of LeFèvre and the study of the Bible brought Farel to the conviction salvation can be found only in Christ, that the Word of God is the only rule of faith. He was amazed he could find in the NT no trace of the pope, a church hierarchy, indulgences, purgatory, the mass, seven rather than two sacraments, a sacerdotal celibacy, or the worship of Mary and saints.

When LeFèvre, was charged with heresy in 1521, he retired but remained an advocate for reformation within the Catholic Church, without separation from Rome. We’ll talk about the Catholic Counter-Reformation in a later episode.

In retirement, LeFèvre translated the NT into French, and published it in 1523. This was virtually simultaneous with Luther’s German NT. Farel and several others of LeFèvre’s students followed him and began preaching a Reformation message under his influence. But Farel proved too radical and was forbidden to preach.

He returned to his hometown and made some converts, including four of his brothers; but the people found his doctrine strange and drove him away. France became dangerous as the persecution of Protestants had begun there as in already had in other places.

Farel fled to Basel, Switzerland. Since Reformation ideas were tolerated there, he held a public disputation in Latin on thirteen issues, in which he affirmed the inspiration of the Scriptures, Christian liberty, the duty of pastors to preach the Gospel, the doctrine of justification by faith, and denounced images and celibacy. This speech led to the conversion of a Franciscan monk named Pellican, a distinguished Greek and Hebrew scholar, who became a professor at Zurich. Farel delivered more public lectures and sermons. But as his popularity grew, so did his bombast, and Erasmus persuaded the town council to brand him a disturber of the peace and expel him.

After bouncing around for a few years as an itinerate preacher, he arrived in Neuchâtel in December, 1529 where he was instrumental in bringing the Reformation to the city.

Farel stopped at Geneva in early Oct. 1532. The day after he arrived he was visited by a number of distinguished citizens of the Protestant French Huguenots. Farel explained to them from an open Bible the Protestant doctrines that would complete and consolidate the political freedom they’d recently achieved. But rather than receive this with joy, they were troubled and demanded Farel and his friends leave! Farel refused. He said he wasn’t trying to create trouble; he was simply a preacher of truth, for which he was ready to die. He showed them letters of reference from several Reformation leaders which made quite an impression.

When the Roman clergy in Geneva began to harass Farel, this only further ingratiated him with the Protestants there. But the Catholics became so angry at Farel’s refusal to budge, the entire city was set on edge. The Council demanded he leave immediately.

He barely escaped as the priests pursued him with clubs. He left covered with spit and bruises. Some of the Huguenots came to his defense, and accompanied him across Lake Geneva.

Since the Reformation in Geneva was gaining ground and the city was seen as key, the Catholics called Guy Furbity, a Dominican doctor of Theology, to come refute the Protestants. He stirred the Catholics of Geneva into a violent mob. All preaching in the City had to be approved by him. You can imagine how Farel felt about that. He returned with a guarantee of protection from the city of Bern, and held another public disputation with Furbity at the end of January of 1534, in the presence of both the Great and Small Councils of Geneva and delegates from Bern. He was unable to answer all Furbity’s objections, but he denied the right of the Church to impose ordinances which were not authorized by Scripture, and defended the position that Christ was the only head of the Church. He used the occasion to explain Protestant doctrines, and to attack Roman church hierarchy. Christ and the Holy Spirit, he said, are not with the pope, but with those whom he persecutes. The disputation lasted several days, and ended in a partial victory for Farel. Unable to argue from the Scriptures, Furbity confessed: “What I preach I cannot prove from the Bible; I have learned it from the Summa of St. Thomas,” meaning of course, Thomas Aquinas.

Farel continued to preach in private homes aa tension grew between Protestants and Catholics. He was the eye of the storm. As more and more Genevans embraced Reformation ideas, priests, monks, and nuns left, and the bishop transferred his See to another city.

In Aug. 27 1535, the Genevan Council issued an edict of the Reformation. That was followed several months later with an even more thorough embrace of Reformation ideals. The mass was abolished, images and relics removed from churches. Citizens pledged themselves by an oath to live according to the precepts of the Gospel. A school was established for the education of the young. Out of it grew the academy of John Calvin. All shops were closed on Sunday. A strict discipline, which extended even to the head-dress of brides was introduced.

This was the first act in the history of the Reformation at Geneva. It was the work of Farel, but only preparatory to the more important work of Calvin. The people were anxious to get rid of the Catholic rule of the Duke of Savoy and the bishop, but had no conception of evangelical religion, and would not submit to discipline. They mistook freedom for license. They were in danger of falling into the opposite extreme of disorder and confusion.

This was the state of things when Calvin arrived at Geneva in the summer of 1536, and was urged by Farel to assume the great task of building a new Church on the ruins of the old. Though 20 years his senior, Farel willingly took a subordinate position to Calvin. He labored for a while as Calvin’s colleague, but was banished from Geneva with him when their reforms were deemed by the City Council as too ambitious and narrow. Calvin then went to Strasburg while Farel accepted a call as pastor at Neuchâtel where he’d worked before.

The remaining twenty-seven years of his life, Farel remained the lead pastor there.