This week’s episode is titled – “Challenge.”

We’ve tracked the development and growth of the Church in the East over a few episodes. To be clear, we’re talking about the Church which made its headquarters in the city of Seleucia, twin city to the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, in the region known as Mesopotamia. What today historians refer to as The Church in the East called itself the Assyrian Church. But it was known by the Catholic Church in the West with its twin centers at Rome and Constantinople, by the disparaging title of the Nestorian Church because it continued on in the theological tradition of Bishop Nestorius, declared heretical by the Councils of Ephesus in 431 and Chalcedon 20 years later. As we’ve seen, it’s doubtful what Nestorius taught about the nature of Christ was truly errant. But Cyril, bishop of Alexandria, more for political reasons than from a concern for theological purity, convinced his peers Nestorius was a heretic and had him and his followers banished. They moved East and formed the core of the Church in the East.

While that branch of the Church thrived during the European Middle Ages, the Western Catholic Church coalesced around 2 centers; Rome and Constantinople. Though they’d reached agreement over the doctrinal issues regarding the nature of Christ and expelled both the Nestorians to the East and the Monophysite Jacobites to their enclaves in Syria and Egypt, the Western and Eastern halves of the Roman Church drifted apart.

The Council of Constantinople in 692 marked one of several turning points in the eventual rift between Rome and Constantinople. Called by the Emperor, the Council was attended only by Eastern Bishops. It dealt with no real doctrinal matters but set down rules for how the Church was to be organized and worship conducted. The problem is that several of the decisions went contrary to the long-held practice in Rome and the churches in Western Europe that looked to it. The Pope rejected the Council. à And the gulf between Rome and Constantinople widened.

This gap between the Eastern and Western halves of the Church mirrored what was happening in the Empire at large. As we’ve seen, Justinian I tried to revive the gory of the Roman Empire in the 6th C, but after his death, the Empire quickly reverted to its path toward disintegration. What helped this dissolution was the emergence of Islam from the southeast corner of the Empire.

Historically, the Arabs were a people of multiple tribes who shared both a common culture and distrust of one another which fueled endless conflict. But the early 7th C saw them united by a new and militant religion. The endless struggles that had kept them at each other’s throats, were merged into a shared mission of setting them at everyone else’s. Why steal from each other in generations of just transferring the same loot back and forth when they could unite and grab new plunder from their neighbors?

And so much the better when those neighbors who used to be too strong to attack, were now in decline and under-defended?

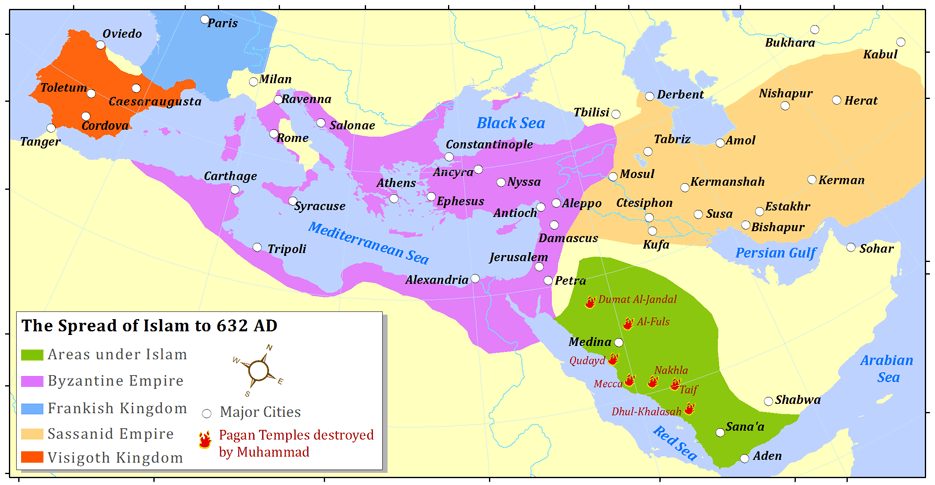

It was a Perfect Storm. The emergence of the Muslim armies in the early 7th C, bursting forth from the furnace that forged them, came right at the time when the once unstoppable might of the Roman Empire was finally a relic of a bygone age. Constantinople was able to hold the invaders at bay for another 700 years, but Islam spread quickly over other lands of the once great Empire; into the Middle East, North Africa, and was even able to get a foothold in Europe when they jumped the Straits of Gibraltar and landed in Spain. In the East, the Muslims swept up into Rome’s ancient nemesis, Persia, and quickly subdued it as well.

It all began with the birth of an Arab named Muhammad in 570.

Since this is a podcast on the history of Christianity rather than Islam, I’ll be brief in this review of the new religion that moved the Arabs out of their peninsula during the 7th C.

Islam marks its beginning to the Hegira, Muhammad’s move from his hometown of Mecca to the city of Medina in AD 622. This began the successful phase of his preaching. Muhammad built a theology that included elements of Judaism, Christianity, and Arabian polytheism.

While there’s much talk today about Islam’s place with Judaism and Christianity as a monotheistic religion, a little research reveals Muhammad really only elevated one of the Arab’s gods over the others – that is Il-Allah, or as it is known today – Allah. Allah was the moon god and patron deity of Muhammad’s Quraysh tribe. The enduring proof of this is the symbol of the crescent moon that adorns the top of every Muslim mosque and minaret and is the universal symbol of Islam.

Muhammad’s new religion included elements of both Judaism and Christianity because he hoped to include both groups in his new movement. The Jews refused his efforts while several Christians joined the new movement. It’s understandable why. The church Muhammad was familiar with was one that had been co-opted by Arab superstition. It hardly resembled Biblical Christianity. It was ripe pickings for the emergent faith. When Islam later ran into more orthodox Christian communities, they refused the new faith. Muhammad was incensed at the Jews and Christians refusal to join, so they became the object of his wrath.

Part of Muhammad’s genius was that he sanctified the Arabic penchant for war by uniting the tribes and sending them on the mission of taking Islam to the rest of the world thru the power of the sword. Loot was made over as a religious bonus, evidence of divine favor.

Islam’s rapid spread across Western Asia and North Africa was facilitated by the vacuum left from the chronic wars between Rome and Persia. Just prior to the Arab conquests, the old combatants had concluded yet another round in their long contest and were exhausted!

In the 2nd decade of the 7th C, the Persians conquered Syria and Palestine from the Romans, took Antioch, pillaged Jerusalem, then conquered Alexandria in Egypt. That means the Persians ruled what had been the 2nd and 3rd most populous cities of the Roman Empire. They conquered most of Asia Minor and set-up camp just across the Bosporus from Constantinople.

Then, in one of the great reversals of history, Emperor Heraclius rallied the Eastern Empire and launched a Holy War to reclaim the lands lost to the Persians. They retook Syria, Palestine, Egypt and invaded deep into Persia. You can well imagine what all this war did politically, environmentally and economically to the region. It left it exhausted. Like a body whose defenses are down, the Eastern Empire was ripe for a new invasion. And look; Oh goodie à Here come the Arabs swinging their scimitars. The Arab advance was nothing less than spectacular.

Muhammad died in 632 and was followed by a series of associates known as caliphs. In 635 the Arabs took Damascus, in 638 they captured Jerusalem. Alexandria fell in 642. Then the Muslim armies turned north and swept up into the demoralized region of Persia. By 650 it was theirs, as were parts of Asia Minor and a large part of North Africa.

The Muslims realized conquering the Mediterranean would require they become a naval power. They did and began taking strategic islands in the Eastern and Central sea. In the 670s with their new navy, they began taking shots at Constantinople but were chased off by a new invention – Greek Fire.

They conquered Carthage in 697, the center of Byzantine might in North Africa. Then in 715, they hopped the Straits of Gibraltar and landed in Spain, bringing the Visigothic rule there to an end. They then crossed the Pyrenees and laid claim to Southwestern Gaul. It wasn’t ill the Battle of Tours in 732 that the Franks under Charles Martel were able to put a halt to the Muslim advance. That also marks the beginning of the ever so slow roll-back of Muslim domination in the Iberian Peninsula.

But what territory Islam lost in the far western reach of their holdings was made up for by their advances in the East. During the 8th C, they reached into Punjab in India and deep into Central Asia.

The major islands of the Mediterranean became coins that flipped from Byzantine to Muslim, then back again. The Muslims even managed to settle a couple of colonies on the coast of Italy. They raided Rome.

These conquests tapered off as the old tendency toward animosity between the Arabic tribes returned. The thing that had united them, Islam, became one more thing to fight over. The main point of contention was over who was supposed to lead the Umma – the Muslim community. Islam fractured into different camps who turned their scimitars on each other, and the rest of the world breathed a collective sigh of relief.

The Church in those lands that now lay under the Crescent moon suffered. Islam was supposed to hold a certain respect for what they called “The People of the Book” – meaning Christians and Jews. Moses and Jesus were considered great prophets in Islam. While pagans had to convert to Islam, Christians and Jews were allowed to continue in their faith, as long as they paid a penalty tax. The treatment of Christians varied widely across Muslims lands. Their fate was determined by the intensity of the rulers’ faith and adherence to Islam. This was largely due to the conflicting instructions found in the Koran about how to treat people of other faiths.

In Islam, later revelation supersedes earlier pronouncements. Early in Muhammad’s career, he hoped to win Christians by persuasion to his cause so he called for kindly treatment of them. Later, when he had some power and Christians proved intractable, he spoke more stridently and urged their forced compliance. Conversion FROM Islam to any other religion was to be punished by execution. But the Koran isn’t set down in a chronological sequence and readers don’t always know which was an earlier and which a later revelation. Some Muslims rulers were stern and read the harsh passages as being the rule. They persecuted Christian and tried to eradicate the Church. Others believed the call to a more merciful relationship with Christians was a higher morality and followed that. Churches were allowed to meet under such rulers, but public demonstrations of faith were banned and no new church building was permitted.

Interestingly, there was a flowering of Arabic culture that took place due to rule by benevolent Muslims. Because Christian scholarship was allowed, the Classics of Greek and Roman civilization were translated into Arabic BY CHRISTIAN CLERGY and SCHOLARS. It was this that led to the emergence of the Arabic Golden Age modern historians make so much of. That such a Golden Age was sparked and enabled by Christian scholars giving Muslims access to the works of classical antiquity is rarely mentioned.

The severe limits placed on the Faith by even lenient Muslim rulers, combined with the harsh treatment of the Church in other places led to widespread loses by the Church in terms of population and influence. Catholic Christians living in North Africa fled north to Europe where they were welcomed by those of similar faith. But the Jacobite Monophysite community was left behind to languish, and the vibrant church culture that had once dominated the region was nearly lost. The resurgent radical Islam of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt is now putting the final nails in the coffin of the Coptic Church, the spiritual heirs to that once vibrant history.

Nearly everywhere Islam spread, it was accompanied by mass defections of marginal Christians to the new faith. Pragmatism isn’t such a modern philosophy after all. Many nominal Christians assumed the single God of Islam was the same as the one God of Christianity and He must favor the Muslims – I mean > look at how successful they are in spreading their religion. Might makes right – Right? // Well, maybe it doesn’t . . . Shhh! Not so loud, the mullahs might hear and their scimitars are sharp.

As many had converted to the newly emergent Christianity under the auspices of Constantine in the early 4th Century, now many converted to Islam under the caliphates in the 7th.

Along with the restrictions placed on those Christians who refused to convert to Islam was added a practice the Muslims picked up from the Zoroastrian rulers of Persia. They required Christians to wear a distinctive badge and prohibited them from serving in the army. That was probably for the best since the army was used specifically to spread the Faith by the sword – the Muslim practice of jihad. But being banned from the military meant they were prohibited the use of arms, and forced to wear distinctive clothing meant easy identification for those hostile elements who saw the presence of Christians as contrary to the will of Allah. Christians became targets of public shame and often, violence. Since conversions FROM Islam were punishable by death, while conversion TO Islam was rewarded, even in the most lenient realms under the banner of Crescent Moon, the church experienced a steady decline.

As Islam settled in and became the dominant cultural force throughout its domains, most of the Christian communities that remained became tradition-bound. They reacted strongly against any innovations, fearing they were dangerous deviations from the Faith they’d held to so tenaciously in spite of persecution. Another reason they rejected change was for fear it might lead to success and the church would grow. Growth meant the Muslim authorities paying closer attention, and that was something they wanted to avoid at all costs. For that reason, to this day the Church in Muslim lands tends to be archaic and bound to traditions practiced for hundreds of years.

I have to take issue with the Allah as Moon God premise you present in this podcast. One does not need to be an apologist for the Muslim faith to recognize that the word Allah is simply the Arabic word for God. Non-Muslim Arabs also have used the word all to mean God, this includes Arab Christians. The certainty of this as simply a general word for the define is found in related languages. In Hebrew for example, we have Elohim. Most authoritatively, in Aramaic, which, obviously was the language Jesus himself spoke, the word is Elah.

Just because there may have been a pre-monotheistic moon god with a similar name establishes nothing. For example the word for God in many romance languages derives from the Latin Deus. That word, ultimately, derives from the same source as the Roman Jupiter (or Deus Pater) or Greek Zeus (also known as Zeus Pater). Of course, no one would think that a Frenchman exclaiming Mon Dieu is invoking the classical thunder god.

Chris, I did a lengthy reply to this several days back and just realized it did not post.

Chris, please see my reply to Kevin.

Ageed. Allah is the generic Arabic word for “God,” literally – The God. It’s a shortened form of al-Ilah.

The question is WHICH of the many Arabic deities did Muhammad mean?

Well – doesn’t the crescent moon that is the universal symbol of Islam mean something and help clarify that?

Doesn’t the black stone that forms the center of the Ka’aba give us a hint?

Maybe you are unaware of the huge debate among missiologists about the appropriateness of using the name “Allah” for God when doing evangelism among Muslims & the people of the middle East, because while it is indeed the generic name for God, it’s associations with the Islamic god so color it that it has no reference to the God of the Bible. A growing number of scholars realize it’s best to drop the name Allah when referring to God because it carries a connotation in the minds of many Arabic speakers of a deity that is totally other, & can’t have a Son.

I have listened to this podcast with great pleasure and always appreciated how you would let the listener know when your own beliefs might be coloring your narrative. So I was disappointed in this episode when you trotted out the old Robert Morey Meme about Allah being a moon God. This is so blatant and patently false that it leads me to question the veracity of the entire series.

Kevin,

Sorry to disappoint you. The reason I did not qualify the remark as opinion is because, to my knowledge, it’s not. It is as presented-a fact. Just because Morey mentions it doesn’t make it categorically false.

Yes, I realize it’s a controversial issue and one refuted by some scholars, but it’s adhered to by others. My research moves me to find it accurate. Al-Ilah, the generic name for “God” among the Arabic tribes morphed into “Allah.” While it’s true there’s considerable debate over just which of the many Arabic deities Muhammad meant, the candidates are Hubal, al-Lat, al-Manat, al-Uzza, al-Rahman & al-Hajar al-Aswad – which was worshiped specifically by the black stone in the Ka’aba.

Kevin, if Allah’s genesis has nothing to do with the moon, can you provide an explanation for why the crescent moon is THE symbol of Islam?

If you can point me to a definitive source that gives the lie to this position, please – help me out.

It’s a symbol of the Ottoman turks. Came to Islam in the 19th century. Here’s a source:

William Ridgeway, “The Origin of the Turkish Crescent”, in The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 38 (Jul. – Dec. 1908), pp. 241-258 (p 241)

I think it is instructive to consider the Islamic views on the matter. They see Allah as an omnipotent deity that was worshipped by Adam, Noah, Abraham, etc. etc. They consider pre-islamic religion to be pagan idolatry. Again, if there is any imagery that is drawn from the earlier traditions, it no more invalidates the Abrahamic character of Islam than does the fact that many Christian depictions of God strongly reaemble classical depictions of Zeus.

As for the vexillology, the earliest Islamic flags and banners were entirely without any symbols, just all black, all white, all green, etc. To the issue of why the crescent is THE symbol of islam, its a heck of a lot easier to draw a crescent than to write the calligraphical symbols of their faith.

I would like to thank Lance for his accurate description of the origin of the word “allah”. I’ve been doing some research lately on Islam and it’s origins. Here are some interesting things to ponder:

The word alah does exist in Hebrew but it is not a proper name and it never refers to God. There is no word ‘alah’ or ‘allah’in the Greek New Testament at all. The word ‘allah’ comes from the compound Arabic word, al-ila. Al is the definite article “the” and ilah is an Arabic word for “god”, i.e. “the god”. It is not a proper name but a generic name.

“allah” also was around before Mohammed:

here are some cites:

“Allah was known to the pre-Islamic Arabs; he was one of the Meccan deities” (Encyclopedia of Islam, ed. Gibb, 1:406)

“The name Allah goes back before Muhammed” (Encyclopedia of World Mythology and Legend, “The Facts on File”, ed. Anthony Mercatante, New York, 1983, 1:41)

The origin of this (Allah) goes back to pre-Muslim times. Allah is not common name meaning “God” (or a “god”), and the Muslim must use another word or form if he wishes to indicate an other than his own peculiar deity” (Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, ed. James Hastings, Edinburgh: T&T Clark,1908, 1:326)

It is well know that in archaeology, the cresent moon was a symbol of worship of the moon god both in Arabia and throughout the Middle East in pre-Islamic times. Many archaeologists have excavated numerous statues and hieroglyphic inscriptions in which a crescent moon is on top of the head of a deity generally a female deity.

The Quraysh tribe which Mohammed was born into was particularly devoted to Allah, the moon god, especially to Allah’s three daughters (Islamic theology does not attest that Allah is a father today) who were viewed as intercessors between the people and Allah.

Also interesting to point out, the literal Arabic name of Muhammad’s father was Abd-Allah. His uncle’s name was Obied-Allah. Anyone would see that his pagan family worshipped Allah, the mood god.

Thanks Brian. I did get some resistance to this episode on these issues.

Lance

Hi, as a Muslim I am listening & enjoying this podcast because I wanted to learn Christian history from a Christian perspective. I have read several books but they were generally from Academics who weren’t Christians themselves thus I though may present their own non-Christian angle. Honestly the information on Islam in this episode was very weak, but I hope you take this as an opportunity to learn Islam from a Muslim’s perspective. Thanks from Canada

Thank you for the kinds words Ibrahim.

I’ve been challenged on some of this in this episode before.

And have to say, have done quite a bit of study on Islam.

Certainly no expert. But have a solid working awareness of the basics and history.

Ibrahim, I’ve looked at this connection between the moon god & Allah, and Morey and so on and have found that his is a spurious argument. We can argue about current meanings of things but we can’t argue about what people used to believe. Facts are facts.

I don’t mean to be argumentative, just that I must stand by what I said in this episode. People can disagree if they want but I have to report on what my research has uncovered.

With Respect,

Lance

I noticed that the audio for this episode does not match the written notes and instead is the audio for the following episode! I can definitely just read the information, but I do really enjoy listening to the podcast and following along. I just wanted to let you know!

Dani,

THANK YOU SO MUCH for pointing that out – fixed now.

Had copied the wrong file link before.

So thankful for the notice.

Lance