This episode of Communio Sanctorum is titled, “Liturgy.”

What comes to mind when you hear that word – “Liturgy.”

Most likely—it brings up various associations for different people. Some find great comfort in what the word connotes because it recalls a time in their life of close connection to God. Others think of empty rituals that obscure, rather than bring closer a sense of the sacred.

The following is by no means meant as a comprehensive study of Christian liturgy. Far from it. That would take hours. This is just a thumbnail sketch of the genesis of some of the liturgical traditions of the Church.

First off, using a broad-brush the word ‘liturgy’ refers to the order and parts of a service held in a church. Even though most non-denominational, Evangelical churches like the one I’m a part of doesn’t call our order of service on a Sunday morning a “liturgy” – that’s in fact what it is. Technically, the word “Liturgy” means “service.” But it’s come to refer to all the various parts of a church service, that is, when a local church community gathers for worship. It includes the order the various events occur, how they’re conducted, what scripts are recited, what music is used, which rituals are performed, even what physical objects are employed to conduct them; things like special clothes, furniture, & implements.

Even within the same church, there may be different liturgies for different events and seasons of the year.

For convenience sake, churches tend to get put into 2 broad categories; liturgical & non-liturgical. Liturgical churches are often also called “high-church” meaning they have a set tradition for the order of the service that includes special vestments for priests & officiants; and follow a pattern for their service that’s been conducted the same way for many years. Certain portions of the Bible are read, then a reading from another treasured tome of that denomination, people sit, stand and kneel at designated times, and clergy follows a set route through the sanctuary.

In a non-liturgical church, while they may follow a regular order of service, there’s little of the formalism and ritual used in a high-church service. In many liturgical churches, the message a pastor or priest is to share each week is spelled out by the denominational hierarchy in a manual sent out annually. In a non-liturgical church, the pastor is typically free to pick what he wants to speak on.

The great liturgies arose in the 4th to 6th Cs then codified in the 6th & 7th. They were much more elaborate than the order of service practiced in the churches of the 2nd & 3rd Cs.

Several factors led to the creation of liturgies à

First: There’s a tendency to settle on a standard way to say things when it comes to the beliefs & practices of a group. When someone states something well, or does something in an impressive way, it tends to get repeated.

Second: Bishops & elders tended to take what they learned in one place and transplanted it wherever they went.

Third: A written liturgy made the services more orderly.

Fourth: The desire to hold on to what was thought to be passed down by the Apostles became a priority. This worked against any desire for change.

Fifth: A devotion to orthodoxy, combined for a concern about heresy tended to sanctify what was old and opposed innovation. Changes in a liturgy sparked controversy.

The main liturgies that emerged during the 5th & 6th Cs bear similarities in structure & theme; even in wording, while also having distinct features.

The main liturgical traditions can be listed as . . .

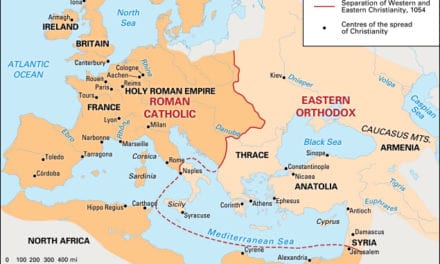

In the East

The Alexandrian or sometimes called Egyptian liturgies.

The West Syrian family includes the Jerusalem, Clementine, & Constantinoplitan liturgies.

The East Syrian family includes the liturgies that were used in the Nestorian churches of the East.

In the West, the principal liturgical families were Roman, Gallican, Ambrosian, Mozarbic & Celtic.

As we saw in Epsidoe 41, Pope Gregory the Great in the 7th C embellished the liturgy & ritual practiced in the Western Roman Church. Elaborate rituals were already a long-time tradition in the Eastern Church, influenced as it was by the court of Constantinople.

If Augustine laid down the theological base for the Medieval church, Pope Gregory can be credited with its liturgical foundation. But no one should assume Gregory created things out of a vacuum. There was already extensive liturgical fodder for him to draw from.

And this brings us to a 4th C document called The Pilgrimage of Etheria – or The Travels of Egeria.

We’re not sure who she was but can narrow it down to either a nun or a well-to-do woman of self-sufficient means from Northern Spain.

She toured the Middle East at the end of the 4th C, then wrote a long letter to some women she call her sisters & friends, chronicling her 3 year adventure. While the beginning and end of the letter are missing, the main body gives a detailed account of her trip, made from extensive notes.

The first part describes her journey from Egypt to Sinai, ending at Constantinople. She visited Edessa, and travelled extensively in Palestine. The second and much longer section is a detailed account of the services and observances of the church in Jerusalem, centered on what the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

What’s remarkable in reading her account is the tremendous sense of freedom and safety Egeria seems to have had as she travelled over long distances in hostile environs. She was accompanied for a time by some soldiers, and no doubt these provided a measure of security. But that she felt safe WITH THEM, is remarkable and speaks to the impact the Faith was already having on the morality of the ancient world.

Remarkable as well was the large number of Christian communes, monks & bishops she met on her travels. Every place mentioned in the Bible already had a shrine or church. As she visited each, using her Bible as a guide, she was shown dozens of places where this or that Biblical event was supposed to have occurred.

I’ve been to the Holy Land several times. I know the many sites today that claim to be the place where this or that Bible story unfolded. Most of the sites are at best a guess. What I found fascinating about Egeria’s account is that already, by the end of the 4th C, most of these sites were already boasting to be the very place. I have to wonder if the obligatory souvenir shop was also hawking wares at each location.

You can’t read Egeria’s chronicle without being impressed with how thoroughly the Church had covered the Middle East in just 300 years, even in isolated locations; places mentioned in passing in the account of the Exodus. Every little town & village mentioned in the Old and New Testaments had a church or memorial and a group of monks ready to tell the story of what happened there. 300 years may seem like a long time, but remember that almost ALL that time was marked by persecution of Jesus’ followers.

Egeria’s account of the liturgy of the church in Jerusalem, occupying the bulk of her record, is interesting because it reveals a pretty elaborate tradition for both daily services & special days like the Holy Week. They observed the hours and Holy Service marking off the day in different periods of devotion led by the Bishop.

Accepted history tells us that the idea of a liturgical year was only just beginning in Egeria’s time. Her description of the practices of the Jerusalem Church community make clear many aspects of the liturgical year were already well along, and had been for some time.

If you’re interested in reading Egeria’s account yourself, you can find it on the net. I’ll put a link in the show notes.

http://www.ccel.org/m/mcclure/etheria/etheria.htm