This 58th Episode of CS is titled – Monk Business Part 1 and is the first of several episodes in which we’ll take a look at monastic movements in Church History.

I realize that may not sound terribly exciting to some. The prospect of digging into this part of the story didn’t hold much interest for me either, until I realized how rich it is. You see, being a bit of a fan for the work of J. Edwin Orr, I love the history of revival. Well, it turns out each new monastic movement was often a fresh move of God’s Spirit in renewal. Several were a new wineskin for God’s work.

The roots of monasticism are worth taking some time to unpack. Let’s get started . . .

Leisure time to converse about philosophy with friends was prized in the ancient world. Even if someone didn’t have the intellectual chops to wax eloquent on philosophy, it was still fashionable to express a yearning for such intellectual leisure, or “otium” as it was called; but of course, they were much too busy serving their fellow man. It was the ancient version of, “I just don’t have any ‘Me-time’.”

Sometimes, as the famous Roman orator Cicero, the ancients did score the time for such reflection and enlightened discussion and retired to write on themes such as duty, friendship, and old age. That towering intellect and theologian, Augustine of Hippo had the same wish as a young man, and when he became a Christian in 386, left his professorship in oratory to devote his life to contemplation and writing. He retreated with a group of friends, his son and his mother, to a home on Lake Como, to discuss, then write about The Happy Life, Order and other such subjects, in which both classical philosophy and Christianity shared an interest. When he returned to his hometown in North Africa, he set up a community in which he and his friends could lead a monastic life, apart from the world, studying scripture and praying. Augustine’s contemporary, Jerome; translator of the Latin Bible known as the Vulgate, felt the same tug, and he, too, made a series of attempts to live apart from the world so he could give himself to philosophical reflection.

Ah; the Good Life!

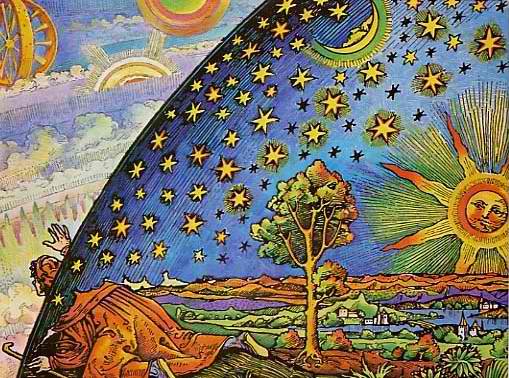

This sense of a divine ‘call’ to a Christian version of this life of ‘philosophical retirement’ had an important difference from the older, pagan version. While reading and meditation remained central, the call to do it in concert with others who also set themselves apart from the world both spiritually and physically was added to the mix.

For the monks and nuns who sought such a communal life, the crucial thing was the call to a way of life which would make it possible to ‘go apart’ and spend time with God in prayer and worship. Prayer was the opus dei, the ‘work of God’.

As it was originally conceived, to become a monk or nun was to attempt to obey to the full the commandment to love God with all one is and has. In the Middle Ages, it was also understood to be a fulfillment of the command to love one’s neighbor, for monks and nuns prayed for the world. They really believed prayer was an important task on behalf of a morally and spiritually needy world of lost souls. So among the members of a monastery, there were those who prayed, those who ruled, and those who worked. The most important to society, were those who prayed.

A difference developed between the monastic movements in the East and West. In the East, the Desert Fathers set the pattern. They were hermits who adopted extreme forms of piety and asceticism. They were regarded as powerhouses of spiritual influence; authorities who could assist ordinary people with their problems. The Stylites, for example, lived on high platforms; sitting atop poles, and were an object of reverence to those who came to ask advice. Others, shut off from the world in caves or huts, sought to deny themselves any contact with the temptations of ‘the world’, especially women. There was in this an obvious preoccupation with the dangers of the flesh, which was partly a legacy of the Greek dualists’ conviction that matter and the physical world were unredeemably evil.

I pause to make a personal, pastoral observation. So warning! – Blatant opinion follows.

You can’t read the NT without seeing the call to holiness in the Christian Life. But that holiness is a work of God’s grace as the Holy Spirit empowers the believer to live a life pleasing to God. NT holiness is a joyous privilege, not a heavy burden and duty. NT holiness enhances life, never diminishes it.

This is what Jesus modeled so well; and it’s why genuine seekers after God were drawn to him. He was attractive. He didn’t just do holiness, He WAS Holy. Yet no one had more life. And everywhere He went, dead things came to life!

As Jesus’ followers, we’re supposed to be holy in the same way. But if we’re honest, we’d have to admit that for the vast majority, holiness is conceived as a dry, boring, life-sucking burden of moral perfection.

Real holiness isn’t religious rule-keeping. It isn’t a list of moral proscriptions; a set of “Don’t’s! Or I will smite thee with Divine Wrath and cast thy wretched soul into the eternal flames!”

NT holiness is a mark of Real Life, the one Jesus rose again to give us. It’s Jesus living in and thru us.

The Desert Fathers and hermits who followed their example were heavily influenced by the dualist Greek worldview that all matter was evil and only the spirit was good. Holiness meant an attempt to avoid any shred of physical pleasure while retreating into the life of the mind. This thinking was the major force influencing the monastic movement as it moved both East and West. But in the East, the monks were hermits who pursued their lifestyles in isolation while in the West, they tended to pursue them in concert and communal life.

As we go on we’ll see that some monastic leaders realized casting holiness as a negative denial of the flesh rather than a positive embracing of the love and truth of Christ was an error they sought to reform.

In the East, while monks might live in a group, they didn’t seek for community. They didn’t converse or work together in a common cause. They simply shared cells next to one another. And each followed his own schedule. Their only real contact was that they ate together and might pray together. This tradition continues to this day on Mount Athos in northern Greece, where monks live in solitude and prayer in cells high on the cliffs, food lowered to them in baskets.

A crucial development in Western monasticism took place in the 6th C, when Benedict of Nursia withdrew with a group of friends to live an ascetic life. This prompted him to give serious thought to the way in which the ‘religious life’ should be organized. Benedict arranged for groups of 12 monks to live together in small communities. Then he moved to Monte Cassino where, in 529, he set up the monastery which was to become the mother house of the Benedictine Order. The rule of life he drew up there was a synthesis of elements in existing rules for monastic life. From this point on, the Rule of St Benedict set the standard for living the religious life until the 12th C.

The Rule achieved a good working balance between the body and soul. It aimed at moderation and order. It said that those who went apart from the world to live lives dedicated to God should not subject themselves to extreme asceticism. They should live in poverty and chastity, and in obedience to their abbot, but they shouldn’t feel the need to brutalize their flesh with things like scourges and hair-shirts. They should eat moderately but not starve. They should balance their time in a regular and orderly way between manual work, reading and prayer—their real work for God. There were to be seven regular acts of worship in the day, known as ‘hours’, attended by the entire community. In Benedict’s vision, the monastic yoke was to be sweet; the burden light. The monastery was a ‘school’ of the Lord’s service, in which the baptized soul made progress in the Christian life.

In the Anglo-Saxon period of English history, nuns formed a significant part of the population. There were several ‘double monasteries’, where communities of monks and nuns lived side by side. Several female abbots, called ‘abbesses’ proved to be outstanding leaders. Hilda, the Abbess of the double monastery at Whitby played a major role at the Synod of Whitby in 664.

A common feature of monastic life in the West was that it was largely reserved for the upper classes. Serfs generally didn’t have the freedom to become monks. The houses of monks and nuns were the recipients of noble and royal patronage, usually because the nobility thought by supporting such a holy endeavor, they promoted their spiritual case with God. Remember as well that while the first-born son stood to inherit everything, later sons were a potential cause of unrest if they decided to vie with their elder brother in gaining the birthright. So these ‘spare’ children of good birth were often given to monastic communes by their families. They were then charged with carrying the religious duty for the entire family. They were a kind of “spiritual surrogate” whose task was to produce a surplus of godliness the rest of the family could draw from. Rich and powerful families gave monasteries, lands and estates, for the good of the souls of their members. Rulers and soldiers were too busy to attend to their spiritual lives, so ‘professionals’ drawn from their own families could help them by doing it on their behalf.

A consequence of this was that, in the late Middle Ages, the abbot or abbess was usually a nobleman or woman. She/He was often chosen because of being the highest in birth in the monastery or convent, and not because of any natural powers of leadership or outstanding spirituality. Chaucer’s cruel 14th C caricature of a prioress depicts a woman who would have been much more at home in a country house playing with her pet dogs.

In these features of noble patronage of the religious life lay not only the stamp of society’s approval, but also the potential for decay. Monastic houses that became rich and were filled with those who’d not chosen to enter the religious life, but had been put there in childhood, often became decadent. The Cluniac reforms of the 10th C were a consequence of the recognition that there would need to be a tightening of the ship if the Benedictine order was not to be lost altogether. In the commune at Cluny and the houses which imitated it, standards were high, although here, too, there was a danger of distortion of the original Benedictine vision. Cluniac houses had extra rules and a degree of rigidity which compromised the original simplicity of Benedictine life.

At the end of the 11th C, several developments radically altered the range of choice for those in the West who wanted to enter a monastery. The first was a change of fashion, which encouraged married couples of mature years to decide to end their days as a monk or nun. A knight who’d fought his wars might make an agreement with his wife that they would go off into separate religious houses. Adult entry of this sort was by those who really did want to be there, and it had the potential to alter the balance in favor of serious commitment.

But these mature adults weren’t the only one’s entering monasteries. It became fashionable for younger people to head off to a monastery where education had become top-rank. Then monasteries began to specialize in various pursuits. It was a time of experimentation.

Out of this period of experiment came one immensely important new order, the Cistercians. They used the Benedictine rule, but had a different set of priorities. The first was a determination to protect themselves from the dangers which could come from growing too rich.

“Too rich?” you might ask. “How’s that possible if they’d taken a vow of poverty?”

Ah à There’s the rub.

Yes; monks and nuns vowed poverty, but their lifestyle included diligence in work. And some brilliant minds had joined the monasteries, so they’d devised ingenious methods for going about their work in a more productive manner, enhancing yields of crops and products. Being deft businessmen, they worked good deals and maximized profits, which went in to the monastery’s account. But individual monks, of course, didn’t profit thereby. The funds were used to expand the monastery’s resources and facilities. This led to even higher profits. Which were then used in plushing up the monastery itself. The monks’ cells got nicer, the food better, the grounds more sumptuous, the library more expansive. The monks got new outfits. Outwardly things technically were the same, they owned nothing personally, but in fact, their monastic world was upgraded significantly.

The Cistercians responded to this by building houses in remote places and keeping them as simple, bare lodgings. They also made a place for people from the lower social classes who had vocations but wanted to give themselves more completely to God for a period of time. These were called “lay brothers.”

The rather startling early success of the Cistercians was due to Bernard of Clairvaux. When he decided to enter a newly founded Cistercian monastery, he took with him a group of friends and relatives. Because of his oratory skill and praise for the Cistercian model, recruitment proceed so rapidly many more houses had to be founded in quick succession. He was made abbot of one of them at Clairvaux, from which he draws his name. He went on to become a leading figure in the monastic world and in politics. He spoke so well and so movingly that he was useful as a diplomatic emissary, as well as a preacher. You may remember he was one of the premier reasons the Crusades were able to rally so many to their campaign.

Other monastic experiments weren’t so successful. The willingness to try new forms of the monastic life gave a platform for some short-lived endeavors by the eccentric. There are always those who think their idea is THE way it ought to be done. Either because they lack common sense or have no skill at recruiting, they fall apart. So many were engaged in pushing forward the boundaries of monastic life one writer thought it would be helpful to review the available modes in the 12th C. His work covered all the possibilities, from the Benedictines and reformed Benedictines, to priests who didn’t live enclosed lives, but who were allowed to work in the world—and the various sorts of hermits.

The only real rival to the Rule of St Benedict was the ‘Rule’ of Augustine, which was adopted by church leaders. These differed from monks, in that they were priests who could be active in the wider social community, for example, by serving in a parish church. They weren’t living under a monastic rule which confined a monk for life to the house in which he was consecrated. Priests serving in a cathedral, for example, were encouraged to live in a city but under a code like the Augustinian rule which was well-adapted to their needs.

The 12th C saw the creation of new monastic orders. In Paris, the Victorines produced leading academic figures and teachers. The Premonstratensians were a group of Latin monks who took on the massive task of healing the rift between the Eastern and Western churches. The problem was, there was no corresponding monastic group in the East.

We’ll pick it up at this point next time.

Monasticism is an important part of Church History because of the huge impact it had shaping the faith of common Christians throughout the Middle Ages and on into the Renaissance. Some of the monastic leaders are the great pillars of the faith. We can’t really understand them without knowing a little about the world they lived in.

As we end this episode, I want to again say thanks to all those listeners and subscribers who’ve “liked” and left comments on the CS FB page.

I’d also like to say how appreciative I am to those who’ve gone to the iTunes subscription page for CS and left a positive review. We’ve developed a large listener base.

Any donation to CS is appreciated.

Finally, for interested subscribers, I want to invite you to take a listen to the sermon podcast for the church I serve; Calvary Chapel Oxnard. I teach expositionally through the Bible. You can subscribe via iTunes, just do a search for Calvary Chapel Oxnard podcast, or link to the calvaryoxnard.org website.

Again let me say “thank you so very much” for this podcast. It blesses me beyond words I can adequately express. I also want to thank you for your “commentary” on what holiness should be, as you shared in this particular podcast. You put into words what my heart has been coming into after many years of walking as a believer. With the best intentions at heart, I’ve made some pretty severe pendulum swings in my walk, and what you’ve shared seems to be the “balance” that I’m finally coming to… although easier said than done. Some habits of thought and behavior are hard to alter. But hearing you speak on this was very much refreshing and encouraging. Thanks again for your labor of love.

Lem, Thanks for the kind words. I so wish we could go back and just live in one of the 8th Century monastic communities for a week to see what life there was like. WE gotta know there HAD to have been guys who really did “get it” and who had astounding joy as they loved & served God by loving & serving their fellow man. How else can we account for the arrival of someone like Francis of Assisi or Brother Lawrence?

What about St. Seraphim of Sarov (d. 1833) or St. Silouan the Athonite (d. 1938)? (I know that they do not fit in the time period you are covering, but still…) The brands of Christianity current in the US have a sadly limited view of what monasticism was, is, and can be. As much as I expected to, I did not hate this episode. I am glad that you found the subject more interesting than you expected, going in.

George,

Thanks for not hating it as much as you anticipated you would. I guess I’ll take that as a compliment.

George, you obviously are a learned person with a depth and breadth of knowledge on Church History that far surpasses mine. I’m surprised you bother listening to CS. Maybe you ought to be producing your own Church History podcast. Have you considered it?

Yes, as you suggest, these people weren’t any where near the timeline I’m dealing with right now. But even then, I’d be digging pretty deep to mention them even if we were looking at modern monasticism. As you well know, we tend to keep things pretty cursory on CS.

Lance

Please forgive my use of a back-handed compliment. You have spoken in the past with some disaproval of “extreme asceticism”, and with your Calvary Chapel connections, it is understandable to hear that point of view. There were some points in this episode where I would read the record somewhat differently than you, but the entire series exhibits a love for the subject matter and more work than I am able to put in.

Blessings to you, Brother.

George,

I apologize if my previous reply looks snarky. It wasn’t intended that way. I was a bit rushed when I composed it and reading just now it does look terse. Please forgive. I was sincere in my remark about you doing a podcast. You obviously has a depth & breadth of knowledge that would be a great asset to others if you could pull it off. Oh well. Maybe one day . . .

Lance