This episode is titled, Taking It Further.

History, or I should say, the reporting of it, shows a penchant for identifying one person, a singular standout as the locus of change. This despite the recurring fact there were others who participated in or paralleled that change. Such is the case with Martin Luther and the Swiss Reformer Ulrich Zwingli. While Luther is the “historic bookmark” for the genesis of the Reformation, in some ways, Zwingli was ahead of him.

Born in Switzerland in 1484, Ulrich Zwingli was educated in the best universities and ordained a priest. Possessing a keen mind, intense theological inquiry coupled to a keen spiritual struggle brought him to a genuine faith in 1516, a year before Luther tacked his 95 thesis to Wittenberg’s door. Two yrs later, Zwingli arrived in Zurich where he spent the rest of his life. By 1523, he was leading the Reformation in Switzerland.

Zwingli’s preaching convinced Zurich’s city council to permit the clergy to marry. They abolished the Mass and banned images and statues in public worship. They dissolved the monasteries and severed ties with Rome. Recognizing the central place the Bible was to have in the Christian life, the Zurich reformers published the NT in their own vernacular in 1524 and the entire Bible 6 yrs later; 4 yrs before Luther’s German translation was available.

Zwingli didn’t just preach a Reformation message, he lived it. He married Anna Reinhart in 1522.

In one important respect, Zwingli followed the Bible more specifically than Luther. Martin allowed whatever the Bible did not prohibit. Zwingli rejected whatever the Bible did not prescribe. So the Reformation in Zurich tended to strip away more traditional symbols of the Roman church: the efficacy of lighting candles, the use of statues and pictures as objects of devotion, even church music was ended. Later, in England, these reforms would come to be called “Puritanism.”

But more than the application of Reformation principles, Zwingli’s bookmark in history is pegged to the Eucharistic controversy his teaching stirred. He was at the center of a major theological debate concerning the Lord’s Table. Between 1525 and 8, a bitter war of words was waged between Zwingli and Luther. During this debate, Luther would write a tract and Zwingli would reply. Then Zwingli would pen a treatise and Luther would reply. This went back and forth for 3 yrs. It was a war fought with pamphlets as the ammunition.

Both sides rejected the Roman doctrine of transubstantiation—that the prayer of a duly authorized priest transformed the elements into the literal body and blood of Christ. Their disagreement centered on Jesus’ words, “This is My body.” Luther and his followers adopted the position known consubstantiation, which says Jesus is present “in, with, and under” the elements and taking Communion spiritually strengthens the believer.

Zwingli and his supporters regarded this as an unnecessary compromise with the doctrine of transubstantiation. They said Jesus’ words had to be understood symbolically. The elements represented Jesus’ blood and body, and Communion was merely a memorial. An important memorial to be sure, but the bread and wine were just symbols.

The debate remains to this day.

It should be noted that during his last years, Zwingli seems to have moved to a new position in regard to Communion. He came to recognize a spiritual presence of Christ in the elements, though reducing the idea to words is a proposition far beyond the capacity of this podcast to do. This later position of Zwingli was the position of Philip Melanchthon, Luther’s assistant and spiritual heir.

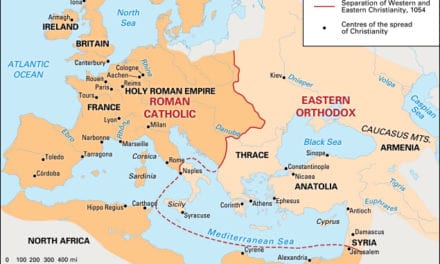

Following hundreds of years of tradition, Zwingli, along with many other Reformers, believed the State and Church should reinforce one another in the work of God; there should be no separation. That’s why the Reformation became increasingly political and split Switzerland into Catholic and Protestant cantons, and eventually saw all of Europe carved up into differing religious regions. The terrible Wars of Religion were the result.

Switzerland at that time was a network of 13 counties called cantons. These were loosely federated and basically democratic. Culturally, the north and east were German, while the west was French, and the south was Italian. The Reformation spread from Zurich, chief city of the capital canton, to the rest of German Switzerland, who were nevertheless reluctant to come under the politic al control of Zurich. Several cantons remained militantly Roman Catholic and resisted Zwingli’s influence for largely economic reasons.

As political tensions grew, several Protestant cantons formed the Christian Civic League. Feeling pressed and threatened, the Catholic cantons also organized and allied themselves with the king of Austria. A desire to avoid war led to the First Peace of Kappel in 1529. But as often happens, once a treaty was hammered out, the only option left was war. Sure enough, two yrs later, five Roman Catholic cantons attacked Zurich, which was unprepared. Zwingli fought as a common soldier in the Battle of Kappel in 1531 and died in the field.

The Second Peace of Kappel hammered out at the end of the year prohibited further spread of the Reformation in Switzerland. Heinrich Bullinger, Zwingli’s son-in-law, took over leadership of the Protestant cause in Zurich and enjoyed great influence across Europe.

An important aspect of Zwingli’s impact on the Reformation was that he cast it along civic lines, with a view to establishing a model Christian community. He persuaded the city council to legislate various details of the Reformation. He aimed at political reform as well as spiritual regeneration.

The inter-canton struggles of this period led to the growing independence of the city of Geneva, which became the home of John Calvin, the other great Reformation luminary. The Swiss Reformation and Zwinglian movement ended up merging with Calvinism later in the 16th C.

Often overlooked in a review of the Reformation are those we might call the REAL reformers – better known as the radical reformers.

Not all those who broke with Rome agreed with Zwingli, Luther, or Calvin. As early as 1523 in Zurich, there were those whose vision of Reform outstripped Zwingli’s. This movement coalesced around 2 leaders: Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz.

On the 21st of Jan, 1525, a little group met in the home of Felix Manz. The Zurich City Council had just ordered Grebel and Manz to stop teaching the Bible. Four days earlier the Council ordered parents to baptize their babies within eight days of birth or face exile. But a group of Zurich’s citizens questioned the practice of infant baptism. They met in Manz’s home to decide what to do. After a time of prayer, they agreed they’d obey what their conscience told them God’s Word said and trust Him to work things out. In an immediate application of that decision, a former priest named George Blaurock asked Conrad Grebel to baptism him in the fashion modeled in the Book of Acts. So, upon confession of His faith in Christ, Grebel baptized him, then Blaurock and Grebel together baptized the others.

Anabaptism, another important expression of the Protestant Reformation, was born.

As a term, anabaptist means “to baptize again.” The Anabaptists stressed believer’s baptism, as opposed to infant baptism. But the term “Anabaptist” refers to diverse groups of Reformers, many of whom embraced radical social, political, economic, and religious views. Some Anabaptist groups are known as the Swiss Brethren, the Mennonites, Hutterites, and the Amish. While those names may conjure up images of buggies, overalls, bonnets and long beards, it’s important to recognize that the Anabaptist tradition lies at the heart of a far larger slice of the Christian and Protestant world. Many modern groups and independent local churches could rightly be called Anabaptist in the bulk of their theology, though ignorant of their spiritual heritage.

While the theology of the Anabaptist groups ended up being widely spread across the doctrinal spectrum, their main stream adhered to the sound, expository teaching of the Scriptures, the Trinity, justification by faith, and the atonement of Christ. What got them in trouble with some of their Reformation brethren was their rejection of infant baptism, which both Catholic and most other Protestant groups affirmed. They argued for a gathered, voluntary church concept as opposed to a State church. They advocated a separation of church and state and adopted pacifism and nonviolent resistance. They said Christians should live communally and share their material possessions. Counter-intuitively to all this, they preached and practiced a strict form of church discipline. Any one of these would mark them as distinct from other Reformation groups; but taken together, the Anabaptists were destined to run into trouble with Lutherans and Calvin’s followers.

That’s what happened in Zurich. Zwingli’s reforming zeal produced an intolerance of his disciples Grebel and Manz who simply wanted to take the reforms further. They tried to convince Zwingli to follow thru into a genuine NT pattern, but all they did was provoke him to urge the City Council to fine, imprisoned, and eventually martyr them and their followers.

The rise of Anabaptism ought to have been no surprise. Revolutions nearly always spin off a radical fringe that feels its destiny is to reform the reformation. Really, that’s what Anabaptism was; a voice calling moderate reformers to take it further; to go all the way into a genuine NT model.

Like most such movements, the Anabaptists lacked cohesion. By lifting up the Bible as their sole authority, they resisted framing a cogent set of doctrinal distinctives. That meant the movement fragmented into several theological streams with no single body of doctrine and no unifying organization prevailing among them. Even the name “Anabaptist” was pinned on them by their enemies and was meant to class them as radicals at best and at worst, dangerous heretics. The campaign to slander them worked well.

In reality, the Radical Reformers rejected the idea of “rebaptism” they were accused of because they never considered the ceremonial sprinkling of infants as valid. They preferred to be called simply “Baptists.” But the fundamental issue wasn’t baptism. It was the nature of the Church and its relation to civil government.

The Radical Reformers came to their convictions as other Protestants had; by reading the Bible. Luther taught that common people had a right to read, understand and apply the Scriptures for themselves, they didn’t need some specially-trained church hierarchy to do all that for them. So, little groups of Anabaptists gathered around their Bibles.

Picture a home Bible study. They discover in the pages of Scripture a very different world from the one the official church had concocted in their day. There was no state-church alliance in the Bible, no so-called “Christendom.” Rather, the Church was comprised of local, autonomous communities of believers drawn together by their faith in Jesus and nurtured by local pastors. And while that seems like a massive “Duh!” to many non-denominational Evangelicals today, it was a revolutionary idea in the 16th C.

You see, though Luther stressed a personal faith for each believer, Lutheran churches were understood as linked together to form THE Church of Germany. Clergy were ordained by a spiritual hierarchy and the entire population of a region were de-facto members of that region’s church. The Church looked to the State for salary and support. In those years, Protestantism differed little from Catholicism in terms of its relationship to the civil authority. If the State was society’s arm with the strength to enforce, the Church was its heart and mind with the insight to inspire and inform.

Or, think of it this way, for 16th C Catholicism, Lutheranism and Calvinism, in society, the State was the body, the Church was the soul. They saw the Radical Reformers insistence that the Church and State were separate as creating a headless monster destined to do great harm.

The Radical Reformers, as we’d suspect, responded with Scripture. Hadn’t Jesus said His kingdom was not of this world? Hadn’t he told Peter to put away his sword? And besides, hadn’t history amply proven that secular, civil power corrupts the Church? All true, but it seems reason and evidence didn’t endear the Radical Reformers to their opponents.

The Anabaptists wanted to reinstall “apostolic Christianity” by which they meant, the Faith as practiced in the NT, where the only members of the Church were those who were genuinely born again, not everyone who happened to be born in a province with a Christian prince.

The True Church, they insisted, is always and only a community of dedicated disciples seeking to live faithfully in the midst of a wicked world.

So that little group that gathered in Manz’s home in January 1525 knew what they were doing was a violation of Zurich’s city council. Persecution was sure to follow. Shortly after the baptism they withdrew from Zurich to the nearby village of Zollikon. There, late in January, the first Anabaptist congregation, the first free church in modern times, was born.

The authorities in Zurich couldn’t overlook what they deemed blatant rebellion. They sent police to Zollikon and arrested the newly baptized and imprisoned them for a time. But as soon as they were released the Anabaptists went to neighboring towns where they made more converts.

Time and warnings passed and the Zurich council ran out of patience. A little over a year later they declared anyone found re-baptizing would be put to death by drowning. “If the heretics want water, they can have it.” Another year went by when the council followed thru on their threat and in Jan, 1527, Felix Manz was the 1st Anabaptist martyr. The authorities drowned him in the Limmat. Just 4 yrs later, the Anabaptists in and around Zurich were virtually wiped out.

Many fled to Germany and Austria where their prospects weren’t any better. In 1529, the Imperial Diet of Speyer declared Anabaptism a heresy and every region of Christendom was obliged to condemn them to death. Between 4 and 5 thousand were executed over the next several years.

The Anabaptists had a simple demand: That a person have a right to his/her own beliefs. What we may not realize is that while that seems an imminently reasonable and assumed axiom for us—it was an idea bequeathed TO US by them! It’s not at all what MOST people thought in the 16th C. No way! No how! The Radical Reformers seemed to Moderate Reformers like Luther and Zwingli to be destroying the very fabric of society. There was simply little conception of a society that wasn’t shaped by the Church’s influence on the State with the State’s enforcement of Church policy.

We hear the Anabaptist voice in a letter written by a young mother, to her daughter only a few days old. è It’s 1573, and the father has already been executed. The mother, in jail, was reprieved long enough to give birth to her child. She writes to urge her daughter not to grow up ashamed of her parents: “My dearest child, the true love of God strengthen you in virtue, you who are yet so young, and whom I must leave in this wicked, evil, perverse world. à Oh, that it had pleased the Lord that I might have brought you up, but it seems that it is not the Lord’s will.… Be not ashamed of us; it is the way which the prophets and the apostles went. Your dear father demonstrated with his blood that it is the genuine faith, and I also hope to attest the same with my blood, though flesh and blood must remain on the posts and on the stake, well knowing that we shall meet hereafter.”

Persecution forced the Anabaptists north. Many of them found refuge on the lands of a tolerant prince in Moravia. There they founded a Christian commune called the Bruderhof which lasted for many years.

A tragic event happened among the Anabaptists in the mid-1530’s that’s another frequent historical trait. The very thing the Lutherans feared, happened.

In 1532, the Reformation spread rapidly throughout the city of Munster. A conservative Lutheran group was the first form of the Reformation to take root there. Then immigrants arrived who were Anabaptist apostles of a shadowy figure named Jan Matthis. What we know about him was written by his critics so he’s cast as a fanatic who whipped the Munster officials into a fury of excitement that God was going to set up his kingdom on earth with Munster as the capital.

The bishop of the region massed his troops to besiege the city and the Anabaptists uncharacteristically defended themselves. During the siege, the more extreme leaders gained control of the city. Then in the Summer of 1534 Jan of Leiden, seized control and declared himself sole ruler. He claimed to receive revelations from God for the city’s victory. He instituted the OT practice of polygamy and took the title “King David.”

With his harem “King David” lived in splendor, but was able to maintain morale in the city in spite of massive hunger due to the siege. He kept the bishop’s army at bay until the end of June, 1535. The fall of the city brought an end to his and the Anabaptist’s rule. But for centuries after, many Europeans equated the word “Anabaptist” with the debacle of the Munster Rebellion. It stood for wild-eyed, religious fanaticism.

Munster was to the Anabaptists what the televangelist scandals of the 80’s were to Evangelicalism; a serious black eye, that in no way reflected their real beliefs. In the aftermath of Munster, the dispirited Anabaptists of Western Germany were encouraged by the work of Menno Simons. A former priest, Menno visited the scattered Anabaptist groups of northern Europe, inspiring them with his preaching. He was unswerving in commanding pacifism. His name in time came to stand for the Mennonite repudiation of violence.

As we end this episode, I want to recommend if anyone wants a much fuller treatment of the Munster Rebellion, let me suggest you visit the Hardcore History podcast titled Prophets of Doom. This podcast by Dan Carlin is an in-depth 4½ hr long investigation of this chapter of Munster’s story.