This episode of CS is titled, “And to the South . . . ” — We move aside now from our review of the Reformation in Europe to get caught up with what’s happening in Africa.

In many, maybe most, popular treatments of Church history, the emphasis is on what’s going on in Europe. That’s what most church-based Christian history courses and many western colleges and seminaries focus on. We’ve already devoted several podcasts to the Church in Asia, both the Eastern or Greek Orthodox church, as well as what’s called “THE Church IN the East,” AKA the Syrian, sometimes and the Nestorian Church.

We’ll soon jump the Atlantic to take a look at the Church in the New World. But before we do, we shift our attention south, to Africa.

As we’ve seen, North Africa was one of the formative cradles of Christianity. That’s where Tertullian, Cyprian and Augustine, 3 of the great Latin Fathers of the Faith kicked it. The Church at Alexandria was 1 of the 4 main churches in the early centuries. Egypt was highly influential in defining what the Faith looked like throughout much of Christendom because of men like Antony and Pachomius; the “desert fathers.” Their strict asceticism is credited with forming the early picture of what popular, but not necessarily Biblical, holiness looked like and which framed the thinking of Christians for hundreds of years. It led in large part to monasticism.

In this episode, we’ll track the course of Christianity as it made its way across the African continent.

The genesis of Ethiopian Christianity rests in Acts 8 where a deacon in the Jerusalem church named Philip was used by God to lead an Ethiopian eunuch and royal treasurer to Faith in Christ. There’s no record of what impact this man had when he returned home, but the fact he made a special trip to Jerusalem in the 1st C reinforces the idea that there was already a Jewish-influenced community in Ethiopia. Like so many of the Jews scattered around the world, meeting in local synagogues, these were prime candidates for the preaching of the Gospel because Jesus was indeed the Jewish Messiah. The Book of Acts shows us it was among God-fearing Gentiles who attended synagogues that the Gospel found it most receptive audience. So it’s likely when the Ethiopian eunuch returned home, he shared what he’d learned and a church was birthed. But not nurtured by apostolic leadership in Jerusalem, it went into decline. Before doing so, it may have left some seeds behind waiting for a later watering.

The best record we have attaches the planting of the church in Ethiopia to a slave named Frumentius around ad 300. Frumentius was on a trading voyage when he was captured by pirates and sold to the king of Axum. He proved of such service to the king, he was granted his freedom 40 years later. He immediately went to Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, telling him of Ethiopia’s need of missionary activity. Athanasius consecrated Frumentius as bishop of Axum. Thus began a long tradition, in which Ethiopian Orthodoxy looked to Alexandria and later, the Egyptian Coptic church to appoint its leaders. This continued all the up to 1959.

Frumentius’s pioneering work was furthered by what are known as the Nine Saints from Syria who arrived about 150 years after Frumentius. Their work saw Ethiopia become a Christian kingdom. The government remained focused on a Christian monarch in several periods of upheaval thru the centuries, till the reign of Haile Selassie in the 20th C.

There are characteristics of Ethiopian Christianity that deserve notice. It was an extremely Jewish form of Christian tradition and for long periods observed a Saturday-Sabbath rather than Sunday as the day of worship. It shared with the Falasha Jews of Ethiopia a great respect for the history of King Solomon and his visitor, the Queen of Sheba. They bore a tenacious legend that, after their meeting, the Ark of the Covenant was removed from Jerusalem and taken to Ethiopia where it was stored in secret. Various reasons were given for this; most notably that as Solomon began his slide into apostasy, a faithful priest recognized the day would come when foreigners would destroy the temple. To preserve the ark, a duplicate was made, switched out with the real ark, which was then packed off for safe-keeping to Ethiopia. This led to the production of multitudes of miniature ‘arks’, called ‘tabot’, displayed in places of Christian worship. The Ethiopian account of the royal meeting between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba is a document called the Kebra Nagast, which dates to the early 6th C. Ethiopian Christians considered themselves Christian–Jews. They retain the practice of circumcision alongside baptism. Monarchs regard their dynasty as from Solomon. One of Haile Selassie’s titles was ‘Lion of Judah’.

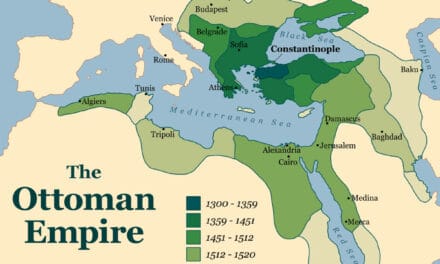

Like the Egyptian church it’s derived from, the Ethiopian church has a strong monastic tradition. The Nine Saints founded a number of communities around Axum; places like Dabra Damo, which lasted 1,000 years. Around 1270, the famous monastery Dabra Libanos became a center of renewal. Axum had a large, 5-aisled cathedral destroyed by Muslims in the 16th C. At that point, the whole kingdom would have become permanently Muslim had it not been for Portuguese military assistance in a decisive battle of 1543.

Much credit for the survival of the Ethiopian church goes to their ancient translation of the Bible into Ge’ez [Gee-ehz]; a musical worship tradition practiced by the laity. Over the centuries different Christian groups have rallied to their aid to assist them against oppressors. Despite their appreciation, the Ethiopian church has resisted attempts to align themselves with any outside group. Estimates are that the Ethiopian Orthodox church has about 45 million members today and is the majority religious group. The 12th and 13th C rock-cut churches of the Lalibela region still delight tourists with the uniqueness of their architecture and the improbability of their construction.

The survival of the church in Ethiopia underlines the tragic fate of the Church next door in ancient Nubia, or what today we know as the Sudan. Nubia possessed a flourishing Christian kingdom from the 8th to 12th C. Centered at the capital of Khartoum, Nubian bishops, like their Ethiopian peers, were consecrated by the patriarch of Alexandria. When a Muslim king ascended the throne, it spelled the end of Nubian Christianity. Best evidence suggests the church in Nubia began as a mission sent out by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian and his wife Theodora in 543. By 580 the entire population were followers of Jesus. But by 1500, the entire region was Muslim and what had been a flourishing church disappeared. In the 1960s, prior to the flooding of northern Sudan for the Aswan dam, excavations revealed the rich remains of Nubian churches.

Remember now back to your world history class in your freshman or sophomore year of High School à What ethnic and national group sailed down the west coast of Africa, looking for a way to get to the rich trading ports of the Indian Ocean?

Right. The Portuguese. Their progress down the west coast of Africa resulted in trading centers at Elmina on the Gold Coast, modern day Ghana, in 1482 and expeditions up the River Zaire in 1483-7. An expedition in 1491 saw a local king named Mbanza Congo, baptized and renamed as Joao I [joe-ow], after the reigning Portuguese king Joao II; Joao is Portuguese for John.

Following King Congo’s conversion, the Christianization of the region continued under his successor, King Mvemba Nzinga, renamed Afonso. He made Christianity the religion of the nobility, taking titles like ‘marquise’ from the Portuguese aristocracy. Afonso’s son, Henrique, was sent to Lisbon for education and was made a bishop in 1521. Unfortunately, he died not long after his return to Africa in 1530.

King Afonso made regular appeals to the Portuguese for assistance in establishing the Christian faith from 1514 onwards. A Portuguese priest of the time left a vivid portrait of Afonso, still regarded in the Congo as the ‘Apostle of the Congo’. He was a skillful preacher who established a tradition of royal preaching. By all reports, this Congolese king was a genuine Billy Graham to his time and people.

Now that’s a very Western-centric way to put it, isn’t it? IT would be just as accurate to say Billy Graham was an American King Afonso, or even better, an American Mvemba Nzinga.

After Afonso’s death in 1543, the story of the Congo is one of missed opportunities. Though he made frequent appeals for missionaries to come and work in Africa, the contest between Spain and Portugal stalled their efforts. Since the Jesuits were international, they arrived in the capital of Sao Salvador and opened a seminary in 1624. A Congolese ambassador visited Pope Paul V in 1608, an event commemorated in a Vatican fresco.

A minor order of the Franciscans called the Capuchins tried to carry on outreach to the Congo, but conditions were brutal and many died. By 1700, Christianity was fading from the region. It wasn’t until Baptist missionaries arrived in the 19th C that things picked up once more.

By the late 18th C, the slave-trade from West Africa to the New World ran into the thousands. After the successful campaign for abolition led by William Wilberforce, with the help of a remarkable African in England, Olaudah Equiano, a British naval squadron patrolled the coast from 1807 searching for slavers. But the Portuguese still exported thousands across the Atlantic to the slave fields of Brazil, as the English had done to the sugar plantations of the West Indies by the notorious ‘middle passage.’

Sierra Leone became a dumping ground for the British Navy’s spoils from captured slavers. The Church Missionary Society, founded in 1799, set to work providing relief and evangelism for ex-slaves. By 1860, 60,000 freed slaves were dropped off at Freetown. But uprooted from their tribal structures and unable to return to their homes, they were gradually settled in what in many cases became model Christian villages.

Among the arrivals in Sierra Leone was a group of 1200 freed American slaves. These had organized themselves into 15 ships at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and arrived singing hymns as they came ashore with their Baptist, Methodist, and other pastors. In time, Methodist life was greatly strengthened by the arrival from England of Thomas Birch Freeman, the son of an African father and English mother. Being of African descent, Freeman was able to survive the West African climate, fatal for European missionaries, and gave long service in West Africa.

Eventually, some of the repatriated Africans of Sierra Leone caught the vision of returning to their tribes with the Gospel. Among them was Samuel Crowther. Crowther had been liberated from a Portuguese slaver in 1821. He was one of the first students at the new missionary college at Fourah Bay. He became a missionary to his branch of the Yoruba tribe in the 1830s, at the same time translating books of the NT. Crowther was part of a growing trend in missions; that of planting indigenous churches that were self-supporting, self-governing ,and self-extending.

Johannes van der Kemp helped found the Netherlands Missionary Society. A retired soldier, he became a doctor before arriving in Cape Town, South Africa in 1799. His arrival among the Boers was like a match lit to a powder-keg. The Boers were Dutch farmers of South Africa who tried to maintain their distance from the British and constant conflict with local tribes.

Van der Kemp was brilliant and upset the conservative-minded Boers with his marriage to a Malagasy slave girl, to say nothing of his virulent opposition to slavery and the oppression of Africans. He immediately went to work bringing the Gospel to South Africans and showed a special care for those displaced by armed conflict.

Arriving in Cape Town from England at this time was Robert Moffatt whose style of mission work was very different from that of the indigenous designs of Crowther and his European friends. Moffat’s philosophy of missions was more old-school. He built a mission compound which sought to preserve a little slice of England inside its fence. Africans were then invited to come TO the missionaries for preaching and teaching of a European-brand of Christianity. He gave 50 years to the mission north of the Orange River.

This was where the famous Scottish missionary David Livingstone spent his first years after arriving in Africa. Livingstone married Moffat’s daughter Mary; and Moffatt guided Livingstone in his early years in the field.

Livingstone became a physician in Glasgow in 1840 and arrived in Cape Town in 1841. His and Mary’s first child died in 1846. They lost another 4 years later. In 1852, Mary took their other children back to Scotland, but this proved a bad move. She moved in with David’s parents. >> In–laws, you know how it goes! Well, things didn’t go well and Mary began tipping the bottle in her loneliness. After Livingstone’s epic journeys of 1853–56 thru the interior of Africa and his triumphant reception back home, they were reunited. Mary accompanied him on his Zambezi expedition of 1858, but died. Livingstone’s eldest son, Robert, also died in 1864 as a soldier in the Union cause of the American Civil War. Though Scottish, Robert Livingstone joined the Union Army to help the cause of abolition; a value he learned from his courageous and monumentally giving father. As you know, David Livingstone was found by the explorer H.M. Stanley in 1871 and died in May 1873. His funeral, paid for by the British government, was held in Westminster Abbey on April 18, 1874, with 2 royal carriages for the family, who included Moffatt, 2 of Livingstone’s sons, and his daughter, to whom he’d been particularly close in his last years.

Livingstone spent his first 11 years at the Moffatt mission-station but felt that style of mission work wasn’t effective. He conceived his plan of exploration, which took him west to the Loanda coast of Angola, then east to the mouth of the Zambezi.

You’ve likely heard the story, true it turns out, that the Africans came to love Livingstone so intensely, because they knew he loved them so much, that when he died, they consented to allow his body to return to his native Scotland, but claimed his heart for Africa.

While there were scattered attempts to take the Gospel into East Africa throughout the centuries, nothing ever really took hold. It wasn’t till Protestant missionaries of the 19th C arrived that a consistent work began. Then the church began to grow in Kenya and Uganda. But Protestants weren’t the only ones bringing the Gospel to East Africa. The Roman Catholic archbishop of Algiers, Charles Lavigerie founded the Missionaries of Our Lady of Africa, known as the White Fathers. A group arrived in Uganda in 1878. This brought a wave of conversions and an outbreak of violence between competing groups of Muslims, Catholics, and Anglicans. Infrequent but brutal atrocities moved the British to send in troops to quell the disturbances and the region became a British protectorate in 1893. The colonial period that followed was a time of mass response to Christianity in the country.