The title of this episode is Push-Back

As we move to wind up this season of CS, we’ve entered into the modern era in our review of Church history and the emergence of Theological Liberalism. Some historians regard the French Revolution as a turning point in the social development of Europe and Western Civilization. The Revolution was in many ways, a result of the Enlightenment, and a harbinger of things to come in the Modern and Post-Modern Eras.

At the risk of being simplistic, for convenience sake, let’s set the history of Western Civilization into these eras of Church History.

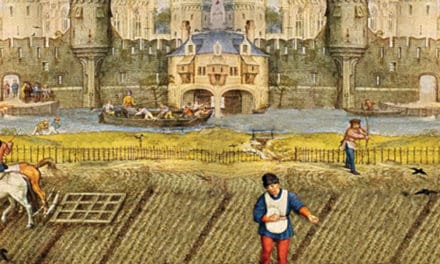

First is the Roman Era, when Christianity was officially opposed and persecuted. That was followed by the Constantinian Era, when the Faith was at first tolerated, then institutionalized. With the Fall of the Roman Empire in the West, Europe entered the Middle Ages and the Church was led by Rome in the West, Constantinople in the East.

The Middle Ages ended with the Renaissance which swiftly split into two streams, the Reformation and the Enlightenment. While many Europeans broke from the hegemony of the Roman Church to launch Protestant movements, others went further and broke from religious faith altogether in an exaltation of reason. They purposefully stepped away from spirituality toward hard-boiled materialism.

This gave birth to the Modern Era, marked by an ongoing tension between Materialistic Rationalism and Philosophical Theism that birthed an entire rainbow of intellectual and faith options.

Carrying on this over-simplified review from where our CS episodes have been, the Modern Era then turned into the Post-Modern Era with a full-flowering and widespread academic acceptance of the radical skepticism birthed during the Enlightenment. The promises of the perfection of the human race through technology promised in the Modern Era were shattered by two World Wars and repeated cases of genocide in the 20th and 21st Cs. Post-Moderns traded in the bright Modernist expectation of an emerging Golden Age for a dystopian vision of technology-run-amuck, controlled by madmen and tyrants. In a classic post-modern proverb, the author George Orwell said, “If you want a vision of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever.”

In our last episode, we embarked on a foray into the roots of Theological Liberalism. The themes of the new era were found in the motto of the French Revolution: “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.”

Liberty was conceived as individual freedom in both the political and economic realms. Liberalism originally referred to this idea of personal liberty in regard to economics and politics. It’s come to mean something very different. Libertarian connects better with the original idea of liberalism than the modern term “liberalism.”

In the early 19th C, liberals promoted the political rights of the middle class. They advocated suffrage and middle-class influence through representative government. In economics, liberals agitated for a laissez faire marketplace where individual enterprise rather than class determined one’s wealth.

Equality, second term in the French Revolution’s trio, stood for individual rights regardless of legacy. If liberty was a predominantly middle-class virtue, equality appealed to rural peasants, the urban working class, and the universally disenfranchised. While the middle class and hold-over nobility advocated a laissez-faire economy, the working class began to agitate for equality through a rival philosophy called socialism. Workers inveighed for equality either through the long route of evolution within a democratic system or the shorter path of revolution via Marxism.

Fraternity, the third idea in the trinity, was the Enlightenment reaction against all the war and turmoil that marked European history till then; especially the trauma that had rocked the continent through endless political, economic, and religious struggle. Fraternity represented a sense of brotherhood that rolled across Europe in the 19th C. And while it held the promise of uniting people in the concept of the universal brotherhood of man under the universal Fatherhood of God, it quickly devolved into Nationalism that would only lead to even bloodier conflicts since they were now accompanied by modern weapons.

These social currents swirled around the Christian Faith during the first decades of the Age of Progress, but no one predicted the ruination they’d bring the Church of Rome, steeped as it was in an inviolable tradition. For over a thousand years she’d presided over feudal Europe. She enthroned dozens of monarchs and ensconced countless nobles. And like them, the Church gave little thought to the power of peasants and the growing middle class. In regards to social standing, in 18th C European society, noble birth and holy calling were everything. Intelligence or achievement meant little.

Things began to heat up in Europe when Enlightenment thinkers began to question the old order. In the 1760s, several places around the world began to feel the heat of political unrest. There’d always been Radicals who challenged the status quo. It usually ended badly for them; forced to drink hemlock or such. But in the mid and late 18th C, they became popular advocates for the middle-class and poor. Their demands were similar: The right to participate in politics, the right to vote, the right to greater freedom of expression.

The success of the American Revolution inspired European radicals. They regarded Americans as true heirs of Enlightenment ideals. They were passionate about equality; and desired peace, yet ready to fight for freedom. In gaining independence from the world’s most formidable power, Americans proved Enlightenment ideals worked.

Then, in the last decade of the 18th C, France executed its king, became a republic, formed a revolutionary regime, and crawled through a period of brutality into the Imperialism of Napoleon Bonaparte.

As we saw in an earlier episode, the Roman Catholic church was so much a part of the old order that revolutionaries often made it an object of their wrath. In the early 1790s, the French National Assembly sought to reform the Church along rationalist lines. But when it eliminated the Pope’s control and required an oath of loyalty on the clergy, it split the Church. The two camps faced off against each other in every village. Between thirty and 40,000 priests were forced into hiding or exile. Atheists recognized the cultural wind was now at their back and pressed for more. Why stop at reforming the Church when you could pry its grip from all society? Radicals moved to remove all traces of Christianity’s influence. They adopted a new calendar and elevated the cult of “Reason.” Some churches were converted to “Temples of Reason.”

But by 1794 this farce had spent itself. The following year a statute was passed affirming the free exercise of religion, and loyal Catholics who’d kept a low profile during the Revolution returned. But Rome never forgot. For now, Liberty meant the worship of the goddess of Reason.

When Napoleon took control, he struck an agreement with the pope; the Concordat of 1801. It restored Roman Catholicism as the quasi-official religion of France. But the Church had lost much of its prestige and power. Europe would never again be a society held together by an alliance of altar and throne. On the other side of things, Rome never welcomed the liberalism reshaping much of Europe’s courts.

As Bruce Shelley aptly remarks, Jesus and the apostles spent little time talking about political freedom, personal liberty, or a person’s right to their opinions. Valuable and important as those things are, they simply do not come into view as values in the appeal of the Gospel. The freedom Christ offers comes through salvation, which places a necessary safeguard on liberty to keep it from becoming a dangerous license.

But during the 19th C, it became popular to think of liberty ITSELF as being free! Free of any and all restraint. Any restriction on freedom was met with a knee-jerk opposition. Everyone ought to be as free as possible. The question then became; just what does that mean. How far does “possible” go?

John Stuart Mill suggested this guideline, “The liberty of each, limited by the like liberty of all.” Liberty meant the right to your opinions, the freedom to express and act upon them, but not to the degree that in doing so, you impinge others’ ability to do so with theirs. Politically and civilly, this was best made possible by a constitutional government that guaranteed universal civil liberty, including the freedom to worship according to one’s choice.

Popes didn’t like that.

In the political and economic vacuum that followed Napoleon, several monarchs tried to re-establish the old systems of Europe. They were resisted by a new and empowered wave of liberals. The first of these liberal uprisings were quickly suppressed in Spain and Italy. But the liberals kept at it and in 1848, revolution temporarily triumphed in most European capitals.

Popes Leo XII, Pius VIII, and Gregory XVI by all accounts were good men. But they ignored the emerging modernity of 19th century Europe by clinging to a moribund past.

There are those who would say it’s not the duty of the Church to keep pace with changing times. The truths of God don’t change. So on the contrary, the Church is to remain resolute in holding to The Faith once and for all delivered to the saints. Faithfulness to the essentials of the Christian Faith is not what we’re referring to here. You can change the flooring in your house without agreeing with the world. Some Popes of the late 18th to mid 19th century seemed to kind of pull the blinds of Vatican windows, trying to keep out the philosophical ideas then sweeping the Continent. That posture toward the wider culture tended to only further alienate the intellectual community.

This early form of Liberalism wanted to address historic evils that have plagued humanity. But it refused to allow the Catholic Church a role in that work as it related to morality and public life. Liberals said politics ought to be independent of Christian ethics. Catholics had rights as private citizens, but their Faith wasn’t welcome in the public arena. This is part of the creeping secularism we talked about in the last episode.

One of the lingering symbols of papal ties to the Medieval world was the Papal States where the Pope was both spiritual leader and civil ruler. In the mid-19th C, a movement for Italian unity began that aimed to turn the entire peninsula into a single nation. Such a revolution wouldn’t tolerate the Papal States. Liberals welcomed Pope Pius IX, who seemed a reforming Pope who’d listen to their counsel. In 1848, he installed a new constitution for the Papal States granting moderate participation in government. This movement toward liberal ideals moved some to suggest the Pope as leader over a unified Italy. But when Pius’ appointed Prime Minister of the Papal States was assassinated by revolutionaries, Pius rescinded the new constitution. Instead of putting the revolution down, it broke out in Rome itself and Pius had to flee. With French assistance, he returned and returned the Papal states to an absolutist regime. Opposition grew under the leadership of King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia. In 1859 and 60 large sections of the Papal States were carved away by nationalists. Then in March of 1861, Victor Emmanuel was proclaimed King of Italy in Florence.

But the City of Rome was protected by a French garrison. When the Franco-Prussian War forced the withdrawal of French troops, Italian nationalists invaded. After a short engagement in September of 1870, Rome surrendered. After lasting for a millennium, the Papal States were no more.

Pius IX holed up in the Vatican. Then in June 1871, King Victor Emmanuel transferred his residence to Rome, ignoring the protests and threatened ex-communication by the pope. The new government offered Pius an annual salary together with the free and unhindered exercise of his religious roles. But the Pope rejected the offer and continued his protests. He forbade Italy’s Catholics to participate in political affairs. That just left the field open to more radicals. The result was a growing anticlerical course in Italian civil affairs. This condition became known as the “Roman Question.” It had no resolution until Benito Mussolini concluded the Lateran Treaty in February 1929. The treaty stipulated that the pope must renounce all claims to the Papal States, but received full sovereignty in the tiny Vatican State. This condition exists to this day.

1870 not only marks the end of the rule of the pope of civil affairs in Italy, it also saw the declaration of his supreme authority as the Bishop of Rome in a doctrine called “Papal Infallibility.” The First Vatican Council, which hammered out the doctrine, represented the culmination of a movement called “ultramontanism” meaning “across the mountains.” Originally referring to the Pope’s hegemony beyond the Alps into the rest of Europe, the term eventually came to mean over and beyond any mountain. Ultramontanism formalized the Pope’s right to lead the Church.

It came about thus . . .

Following the French Revolution (and here we are yet again, recognizing the importance of that revolution in European and world affairs) an especially strong sense of loyalty to the Pope developed there. After the nightmare of the guillotine and the cultural trauma of Napoleon’s reign, many Catholics came to regard the papacy as the only source of civil order and public morality. They believed only popes were capable of restoring sanity to society. Only the papacy had the power to guide the clergy to protect religion from political coercion.

Infallibility was suggested as a necessary prerequisite for an effective papacy. The Church had to become a monarchy adjudicating God’s will. Shelley says as sovereignty was to secular kings, infallibility would be to popes.

By the mid-19th C, this thinking attracted many Catholics. Popes encouraged it in every possible way. One publication said when the pope meditated, God was thinking in him. Hymns appeared that were addressed, not to God, but to Pius IX. Some even spoke of the Pope as the vice-God of humanity.

In December 1854, Pius IX declared as dogma The Immaculate Conception; a belief that had been traditional but not official; that Mary was conceived without original sin. The subject of the decision was nothing new. What was, however, was the way it was announced. This wasn’t dogma defined by a creed produced by a council. It was an ex-cathedra proclamation by the Pope. Ex Cathedra means “from the chair,” and defines an official doctrine issued by the teaching magisterium of the Holy Church.

Ten years after unilaterally announcing the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, Pius sent out an encyclical to all bishops of the Church. He attached a Syllabus of Errors, a compilation of eighty evils then in place in society. He declared war on socialism, rationalism, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, public schools, Bible societies, separation of church and state, and a host of other so-called errors of the Modern Era. He ended by denying that “the Roman pontiff ought to reach an agreement with progress, liberalism, and modern civilization.”

It was a hunker down and rally round an infallible pope mentality that aimed to enter a kind of spiritual hibernation, only emerging when Modernity had impaled itself on its own deadly horns and bled to death.

Pius saw the need for a new universal council to address the Church’s posture toward Modernity and its philosophical partner, Liberalism. He began planning for it in 1865 and called the First Vatican Council to convene at the end of 1869.

The question of the definition of papal infallibility was all the buzz. Catholics had little doubt that as the successor of Peter the Pope possessed special authority. The only question was how far that authority went. Could it be exercised independently from councils or the college of bishops?

After some discussion and politicking, 55 bishops who couldn’t agree to the doctrine as stated were given permission by the Pope to leave Rome, so as not to create dissension. The final vote was 533 for the doctrine of infallibility. Only 2 voted against it. The Council asserted 2 fundamentals: 1) The primacy of the pope and 2) His infallibility.

First, as the successor of Peter, vicar of Christ, and supreme head of the Church, the pope exercises full authority over the whole Church and over individual bishops. That authority extends to all matters of faith and morals as well as to discipline and church administration. Consequently, bishops owe the pope obedience.

Second, when the pope in his official capacity, that is ex cathedra, makes a final decision concerning the entire Church in a matter of faith and morals, that decision is infallible and immutable and does not require the consent of a Council.

The strategy of the ultramontanists, led by Pius IX, shaped the lives of Roman Catholics for generations. Surrounded by the hostile forces of modernity; liberalism and socialism, Rome withdrew behind the walls of an infallible papacy.