His family name was “Black Earth,” as in the rich, fertile soil around his hometown. In German, Schwartzerdt. His first name was Philipp. He was born in Feb of 1497 at Bretten in SW Germany. His father was an armorer for an important German Count.

Though tiny for his age, Philipp was brilliant. It seemed his body put all its energy into the development of his mind rather than his increasingly misshapen body. So at the age of only 10 he joined the scholars at the school of Pforzheim where he learned Latin, Greek and was introduced to Classical philosophy. When it became clear Philipp was something of a prodigy, his well-known humanist uncle Johann Reuchlin took a hand in his education as well. It was he who suggested the burgeoning young scholar follow the humanist fashion of the time and translate his German last name of Schwartzerdt into the Greek Melanchthon.

When at the age of 11, both his father and grandfather died within a few days of each other, Philipp moved in with his grandmother. The next year, at aged 12, He entered the University of Heidelberg where he studied philosophy, rhetoric & astronomy. He quickly made his mark as a scholar of Greek, but was denied his master’s degree for being too young. Shifting to the school in Tübingen, he continued his studies in law, mathematics and medicine.

He was finally granted his Master’s when he turned 19 and began studying theology. Under the influence of humanists like his uncle and Erasmus, Melanchthon became convinced true Christianity was something very different from the dry scholasticism of the Academics.

When his attempts at reform were opposed in Tübingen, he accepted a call from Martin Luther to teach in the University at Wittenberg. At the ripe old age of 21, he took on the role of Professor of Greek. As he studied Scripture he became increasingly convinced Luther’s ideas were theologically sound. There’s a good chance the young Melanchthon helped clarify some of Luther’s early ideas. He went with Luther to Leipzig for a debate with the Catholic Apologist Johann Eck in 1519. Though he only attended as a spectator, he inserted some of his own comments into the debate. Those comments were so telling, Eck felt the need to respond. After returning to Wittenberg, Melanchthon published an effective reply, basing his retorts in Scripture.

When it became clear Philipp was a settled fixture at the University in Wittenberg and was proving himself an able assistant to Luther, the town’s mayor gave consent for his daughter to marry him.

In 1521, Melanchthon’s lectures on Romans in the University became the basis of the Reformation’s first volume on dogmatics, titled Theological Common Places. Seeing several revisions over the following years, the work dealt with themes like the relationship of the law and gospel, the bondage of the will, and justification by faith.

From the outset of his tenure as Luther’s theological side-kick, Melanchthon set a priority on educational reform. He advocated a need for fluency in Greek in theological training and a restructuring of universities along humanist lines. His plans were implemented in the reordering of the schools at Heidelberg & Tübingen, as well as new school at Marburg and Königsberg. Along with Luther, he called for each town to have a public school for the education of its young.

In the last episode, we noted Luther’s increasing cantankerousness as he aged. Some historians attribute this onerousness to his failing health and the constant pain his last few years saw him in. But even as a younger man, Luther was given to bouts of moodiness that swung between mania and depression, sometimes wildly! Philipp’s even-keeled and exceedingly moderate nature seemed the perfect foil to Luther.

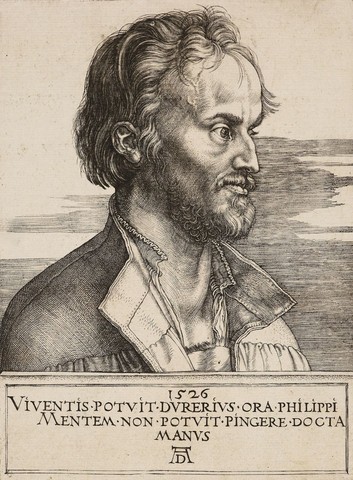

Three famous painters gave their skills to capturing Melanchthon. Holbein, Cranach, and Albrecht Dürer, whose image seems more an attempt to capture Philipp’s spiritual essence than his actual appearance. Contemporaries remarked Dürer capably achieved his goal. These images and the descriptions we have of him present a man who was likely not taller than 4’9” and somewhat misshapen. He was rarely in good health but was able to accomplish as much work as he did because of his well-honed work habits and the extraordinary discipline he exercised. Though Melanchthon could have used his position to great personal advantage, he never accumulated wealth or possessions, but was known for his generosity and hospitality.

His marriage was happy. He called his home “a little church,” & peace was always found there by visitors. There was genuine affection between Philipp and his wife and 4 children. One visitor remarked on his stay with the Melanchthons that he happened by one of the rooms to see Philipp rocking a cradle with one hand while reading a book in the other.

Master Melanchthon had many friends with whom he conversed often, frequently via correspondence, in which he reveals far more of himself and his ideas than he ever did publicly. In fact, he was so generous with his thoughts he frequently wrote speeches & treatises for others, granting them permission to claim them as their own.

Melanchthon eschewed all jealousy, envy, slander, & sarcasm, though being the keen intellect he was, and dealing with oft times obstinate theological opponents he did we can be sure his witty repartee would have been entertaining. To put it succinctly, Melanchthon was The scholar’s Scholar. We’ve probably all heard of, maybe even known, those people who have to be, or think they are, the smartest person in the room. With Melanchthon, he aspired to be, not the smartest, though there’s little doubt he was, but his goal was to be the noblest, the most honest & decent soul in the room. To that end he was brutal in his self-assessment, even to the point of acknowledging his faults to his opponents and critics.

After the Diet of Worms and the obvious break with Rome it clearly meant, Luther seemed content to go his way and take the Church in Germany with him. Then, when other Reformers differed from Luther’s positions on various issues, he seemed willing to split from them as well. Melanchthon worked hard at affecting a reconciliation with both papists and other Reformers, if only they would be willing to negotiate on the basis of Scripture. He & Luther took part in an meeting at Marburg in 1529 with the Zwingli and the Swiss Reformers in an attempt to find a common ground. The Colloquy blew up over their different understandings of the nature of the Eucharist. Melanchthon was able to hammer out agreement with Martin Bucer and Southern Germans on the same issue in the Wittenberg Concord in 1536. He contributed to the 13 Articles Lutherans and Anglicans agreed on 2 yrs later. Having achieved unity with Bucer, the 2 participated in discussions at Hagenau & Worms that eventually led to a monumental Colloquy at Regensburg of 1541. It was there that Cardinal Contarini made a serious bid for reconciliation with the Reformers, When it became clear there were issues both sides could NOT compromise on, the split between Rome and Protestants was final.

While Melanchthon seems a committed Ecumenist in these efforts, a decade later when Thomas Cranmer called for a Reformation-wide ecumenical conference in London, he was less enthusiastic. But there’s good reason for that. He was being accused by hardcore supports of Luther of betraying the cause in weakening Lutheran teaching.

And Philipp’s desire for harmony ought not be understood as his being soft on error. As early as 1522, he argued with Luther’s other assistant at Wittenberg, Andreas Carlstadt who, while Luther was in hiding at Wartburg, assumed control of the Reformation movement in Luther’s absence. Carlstadt’s attitude was that the reforms ought to go forward as swiftly as possible. The problem was, the nobles and rulers who were generally in favor of a break with Rome, found the pace of reform Carlstadt urged too much too soon. Even Luther advocated a slower pace. So he left the Wartburg to return to Wittenberg and dress Carlstadt down. Andreas stayed for a time but, frustrated that the Reforms he knew were needed weren’t being enacted swiftly enough, he left to spread his ideas of Radical Reformation across German & Switzerland. He eventually landed in in the University of Basel.

Along with Luther, Melanchthon was instrumental in formulating the 1530 Augsburg Confession defining the tenants of Lutheranism. In 1540, Melanchthon issued a revised edition of the Confession with edits many Lutherans found objectionable. He was accused by Matthias Flacius of selling Luther out after the great Reformer’s death. Melanchthon adopted a more moderate view than Luther on predestination and the nature of the Lord’s Presence in Communion. His supporters were scornfully called Philippists. These attacks caused the gentle and uncontentious soul considerable distress in his last years. But after his death in 1560, Melanchthon’s essential unity within Lutheranism was vindicated and he was buried beside his friend.

Between Luther & Melanchthon, the later was more the scholar while the former was more the man of action. The steady Melanchthon was the perfect foil to the mercurial Luther. Their friendship owed much to that fact as each recognized the value the other very different style provided for the massive undertaking they’d assumed. While this may be over-simplifying it, we might say Luther was the face and voice of the Early Reformation while Melanchthon was its brains and heart. Melanchthon’s role was best served when he was the quiet one behind the scenes. When Luther was gone and he was called on to step up and take the lead, he proved unequal to the task. Make no mistake, no one doubted his piety & integrity. It’s just that he did not possess the force of character Luther had.

Still, there’s a case to be made that had it not been for Philipp Melanchthon, there wouldn’t have been a Martin Luther and the Reformation as we’ve come to know it.

So – the world would be a very different place.

Lance, this page, 500 Years – Part 04, doesn’t have a download link. Could you fix this? I get the podcasts manually rather than using iTunes or an aggregator. Thanks in advance, and thanks for putting these together.

Done