Welcome BACK to Communion Sanctorum: History of the Christian Church.

We ended our summary & overview narrative of Church History after 150 episodes; took a few months break, and are back to it again with more episodes which aim to fill in the massive gaps we left before.

This time, we’ll do series that go into detail on specific moments, movements, people, places, and other topics.

The title of this episode is The First Centuries – Part 1.

Ask almost anyone with at least a vague awareness of the early years of the Christianity, and they will likely tell you it was a time of intense persecution. Ask how many believers were put to death and the number will range from tens of thousands to a few million.

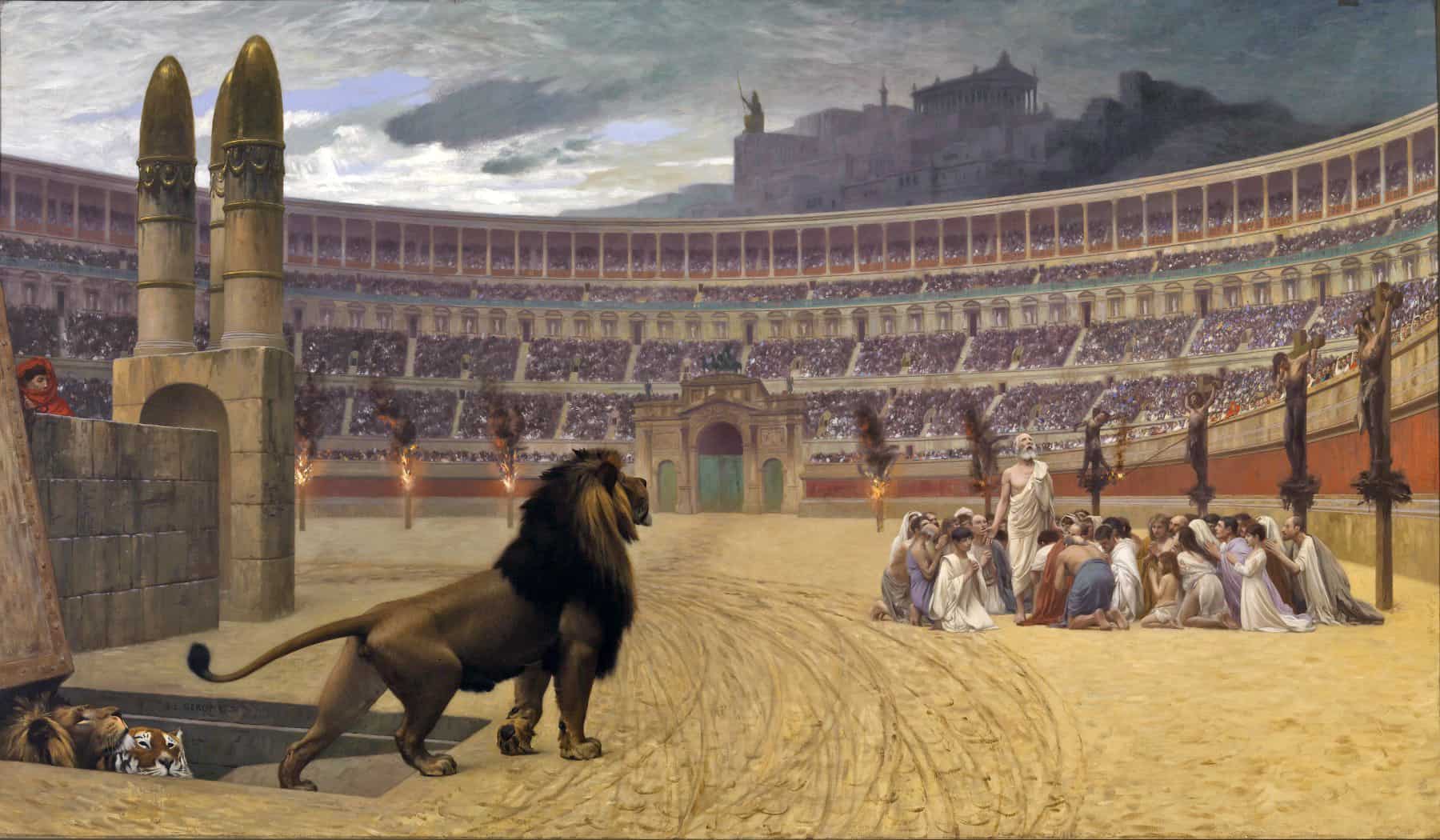

From stories, movies, and paintings of the era, many have the mental image of a mass of defenseless Christians dressed in white, huddled on an arena floor, surrounded by hungry lions. The stands are packed with spectators shouting for blood. But that image, common as it may be, is rather misleading. Did it happen? Undoubtedly. But it wasn’t the ubiquitous scene many assume. Before the dawn of the 3rd C, official imperial attempts to eradicate Christianity were largely unorganized and lukewarm. Roman emperors were rarely the terror to the Faith popular literature has made them. I say rarely, because there were some notable exceptions prior to the 3rd C. After that, things changed dramatically. Some emperors delighted in tormenting Jesus’ followers. Ending Christianity in the most brutal manner seems to have been a major focus for some of them.

Why did Rome persecute Christians? And why is it the popular concept of this time that it was an Era of Martyrs?

It’s best to get at this by backing up a bit to consider Rome’s attitude toward religion. And how are we to do that pray-tell? For attitudes toward religion vary from person to person, and time to time. Among the ancients; Roman, Greek, Jew, Parthian, or whatever, there were those who were devout, the profane, and a whole spread of shades of piety from one end of the religious spectrum to the other. What we’re considering here is the basic Roman civic approach to religion.

It might surprise the modern student to learn that political leaders of Rome served a religious function that was part & parcel of their political task. Their civic duties included cultic rituals. Roman religion was heavily invested in public ceremonies and sacrifices. Personally held religious beliefs weren’t as important as most modern religions regard them. What was important, pre-eminently so, was the possession of pietas. Pietas was religious duty. It meant honoring the sacred Roman traditions in the accepted way. The English word piety is derived from Pietas. But piety wasn’t an option for any Roman who desired to climb the political ranks. It was an absolute essential and something to be demonstrated publicly.

Pietas was THE distinguishing virtue of Rome’s founding hero, Aeneas, who’s given the epithet of “pius” by Virgil in the Aeneid. Cicero elevated pietas to the place Christians would later assign Agape. It was the duty a good Roman was to show to the gods and his fellow man. And by doing so, ensured the safety and prosperity of the State.

Romans of the 2nd C BC to the 4th AD saw themselves as owing a debt of gratitude to their ancestors who embodied the virtues they treasured. It seems our time isn’t the only one that looks to a past Golden Age of yesteryear when “all the women were strong and the men were good-looking.” Romans assigned themselves a custodial roll in preserving the traditions of their ancestors. And not just theirs. They expanded that custody over the traditions of those they conquered. So though they despised the Jewish religion for its seeming irreligious monotheism and refusal to cast Yahweh’s form – because it was an ancient belief, it came under their protection, as did several other Eastern faiths that were too divergent from that of the Greeks and Romans to allow for inclusion in the Roman pantheon.

Christianity was different. It was originally regarded by Rome as a Jewish reform movement; something Jewish leaders would have to deal with within their esoteric and opaque system.

What worried Rome was the rapidity by which the new faith grew. That, and it defied some of Rome’s most cherished ideas about how religion ought to be conducted. Rome was all about the PUBLIC display of ritual. Religion was a community thing. Christians, on the other hand, were secretive. They conducted their services in private and were reluctant to talk publicly about what they did behind closed doors. That reluctance owed to the wild & salacious rumors spread by critics. Calumny began early for Christians. In some places, Jewish opponents, jealous at the success of Christian evangelism, twisted aspects of the Christian message into accusations and whispered them in the ears of officials. Things like, Christians practiced cannibalism, because of the Lord’s Table. It was said they were incestuous, because they held what were called “Love Feasts” where they referred to each other as “brother and sister.” And most damning, was the pagan perception that Christians were in reality practical-atheists. That charge is incomprehensible to modern believers contending with the likes of Dawkins & Harris and their New Atheist compatriots. But in the early centuries, Christians were regarded by their pagan neighbors as atheists precisely because they believed in only ONE God, rather than a plethora.

Though believers tried to dispel these damning mis-conceptions, they lived on. As has been said; A lie travels half-way round the world before truth has put its shoes on. So Christians sequestered themselves behind closed doors and met in secret to conduct their clandestine meetings.

The popular Roman mentality toward religion was that it needed to be practiced in public as an expression of the community’s devotion to the gods, who’d reward this public piety with divine favor. It was relatively easy for them to accept the faiths of those they conquered since they already believed in a multiplicity of deities. What matter that there were now a few more?

That policy of tolerance for the religions of their conquests was sorely tried when it came to the Jews. Though many Romans despised the monotheism of Judaism, toleration was begrudgingly given simply on the basis of the antiquity of the Jewish faith. That toleration was strained to the breaking point under the reign of the mad Emperor Caligula who demanded to be worshipped as a god. Then after the First Jewish–Roman War of AD 66-73, the Jews were allowed to practice their religion only so long as they paid a new tax, the “fiscus Judaicus” ON TOP OF the exorbitant taxes that had sparked their revolt in the first place.

There’s debate among historians over whether the Roman government simply saw Christianity as a sect of Judaism prior to Emperor Nerva’s modification of the fiscus Judaicus in 96. From then on, Jews had to pay while Christians didn’t. SO that seems to suggest an official distinction was made between the 2 groups.

A measure of the Roman disdain for Christianity came from the belief that it was bad for society. In the 3rd C, the Neoplatonist philosopher Porphyry labelled Jesus’ followers as impious & anti-social atheists. Their impiety was located, not in what we’d call traditional morality, but in their refusal to engage in the public religious rituals that were understood by the pagan world as a way to gain the favor of the gods.

Once Christians were distinguished from Jews, the Faith was no longer grand-fathered into reluctant acceptance. No – it became “superstitio.”

For Romans, superstition had a dangerous connotation; far more so that in today’s parlance. It meant religious practices not just different form the norm; they were corrosive to society. Superstition was a set of beliefs that if embraced, dehumanized someone. If enough embraced them and were detached from their humanitas, society would unravel; an ancient spiritual zombie apocalypse. Roman squelching of such dangerous superstitions happened in 428 BC when an unnamed group was eradicated for having caused a damaging drought. In 186 BC, the Romans moved against initiates of the cult of Bacchus when they got unruly. And of course, there’s the famous Roman campaign against the Druids.

The intensity of Christian persecution depended upon how dangerous they were deemed to be by the local official responsible for conducting such oversight. To be frank, Christian beliefs didn’t endeared them to many officials. Think about it. They . . .

1) Worshipped a convicted criminal,

2) Refused to swear by the emperor’s genius,

3) Railed against Roman depravity in their writings,

4) And conducted their suspicious services in private.

In his Apologeticus, addressed to the magistrates of Carthage in the Summer of 197 AD, the early church father Tertullian remarked, “We have the reputation of living aloof from crowds.”

One of the more frequent word used to describe Christians in the NT is hagios, translated “saints.” Literally = holy ones. Bu the root of the word means to be different, set-apart. If something is holy, it’s different from other things. That difference lies in it’s purpose. It’s for God; dedicated exclusively to Him. So, a temple is holy because it’s different from all other buildings; the Sabbath is holy because it’s dedicated to God. Christians are saints, because they belong to God. Jesus’ followers felt this distinction keenly; they embraced it, knowing it set them at odds with their pagan neighbors.

It’s human nature to regard those who are different with suspicion. So the more seriously early Christians took their faith the more hostility they faced. Simply by living in obedience to Jesus, Christians condemned paganism. Christians didn’t run around wagging their fingers or tongues in condemnation of unbelievers. Nor did they advocate and promotes a self-righteous superiority. It just that the Christian ethic revealed the shabbiness of a pagan life.

If that’s all the Christians were guilty of though, persecution would not have broken out against them in such fury. What sparked it was their vehement rejection of the pagan gods. The ancient world had deities for everything. There was a goddess for sowing & another for reaping. There was a god for clear skies and another for rain. Mountains had gods, as did trees & rivers & valleys. For Christians, most of who had at one time worshipped these deities, they were a fiction! And it would be one thing to go quietly about their business with that view, you know, keeping their religion to themselves. But pagans wouldn’t let them. Because every meal began by pouring out a few drops of wine as an offering to the pagan gods. Feasts & parties were held in a temple after sacrifice. The invitation was to dine at the table of some god. It was an ancient version of Chuck E Cheese. But instead of ignoring the dated mechanical rodent, you had to worship it before being allowed to eat your pizza. Christians simply couldn’t attend. When she or he turned down the invitation, they were reviled as rude & anti-social.

There were other events and gatherings Christians avoided because they considered them inherently immoral. They weren’t alone in that assessment. Many moral pagans objected to them as well. Gladiatorial contests are an example. In theaters across the empire, Romans made prisoners & slaves to fight to the death for amusement & entertainment of the crowd.

Refusal to practice idolatry led to financial difficulties. What was a mason to do if as a believer he refused to work stones for a pagan temple or a tailor balked at making a robe for a heathen priest, or a baker refused to make a cake for a . . . never mind.

Tertullian forbade Christians teaching school, because it meant using books with stories of the gods.

As I share that little piece of history, let’s be cognizant of the almost certain reality that Tertullian’s position was in all likelihood not something all believers, and not necessarily even all leaders agreed with. Truth be told, his may have been a minority opinion. The problem is we just don’t have much evidence of what the rest of the Church held regarding this. There was no tirade of tweets one February in the 3rd C over what occupations Christians could and couldn’t fill. It wasn’t a topic people blogged on. No Facebook pages were devoted to it. All we have is Tertullian’s remark. Maybe his pastoral peers disagreed and sent him pointed emails about it. Forgive the anachronism; I take it you get my point.

The larger point for us to glean is that during a time of widespread and aggressive paganism that REQUIRED Christians to go along to get along, many believers found themselves stepping away from public and civil life because in the contest with remaining faithful to Jesus, their conscience demanded it.

Everywhere Christians turned their lives and faith were on display because the Gospel introduced a revolutionary new attitude toward life. This was exhibited most clearly in the realms of Sex, Slaves, and Children.

The Church of the Modern Era has often endured scorn for its old-fashioned views on the sanctity of marriage & marital physical intimacy. That isn’t a criticism early Christians faced, at least from most moral philosophers. On the contrary, ancient Roman moral pundits lamented the abysmal sexual immorality of their times. Raising the sanctity of marriage, along with attitudes toward marital fidelity, was one of the Emperor Augustus’ pet projects. Christianity, infused as it was with a Biblical view of marriage and sex, regarded the body as the temple of the Holy Spirit, withy marriage as a picture of the Church’s union with Christ. Couples who lived out the Gospel in their homes exhibited a quality of life pagans longed for. But it marked them as radically different; and we all know how the mass reacts to that!

Slavery was another matter altogether. It was here that Christianity was regarded as a dangerous force for it attributed dignity to all people regardless of status or state. It’s reported that when Christians met for their distinctive services, masters and their slaves shed the distinctions that marked their lives just before and after the service. Greco-Roman culture might regard slaves as mere living tools, as Plato described them. But Christians esteemed slaves as of equal value with the free. In a society stratified by endless causes for division, the followers of Jesus bore a shocking disregard for those differences. But with the horrors of periodic slave uprisings still fresh in the collective memory, outsiders came to regard the Christian message as dangerously subversive to the social order.

The attitude seemed to be à “Hey, look; it’s great the Christians see all people as equal yet are able to maintain the traditional roles our legal system has imposed. But we now that at some point, if more people go in for this Christian thing, the salves will reach a critical mass and will rebel again. Last time they did, I lost 2 friends and I don’t want to go through that again.”

The sanctity of human life that framed the core of the Christian attitude towards slaves & slavery applied toward children, and in particular, to infants. Unlike their neighbor-pagans, Christians refused to leave their unwanted or physically distressed children in some out of the way place to be left to die of exposure, or to be carried off by traffickers who’d invest a little food now for the pay-off of selling or using them later. In fact, not only did Christian refrain from this barbaric practice, they often rescued such exposed infants and raised them as their own, which of course put an additional financial burden on already strained incomes.

We’ll halt here and pick it up at this point in the next episode. We’ll begin by taking a look at the first systematic persecution under Nero in AD64.

Good to have you back!! Looking forward to this more “in depth” look at the History of the Christian Church.

Just came across your site, and enjoyed your podcast! In addition to child abandonment, Christians also took a firm stand against abortion. The Didache lists both abortion and infanticide in it’s list of major sins.

Indeed. All because of the sanctity of life early Christians held.

Which historically is really quite surprising when we realize the vast majority of Gentiles in the Early Church of that region were Greco-Roman pagans by culture.

I may do a series in how the Christian Worldview came into being and what a radical departure it was from the pagan worldview of the dominant Greco-Roman culture.