This 125th episode of CS is titled A Second Awakening.

I usually leave this announcement for the end but will insert it here at the beginning.

Donations to keep the CS host site up are welcome and needed. You can do so at sanctorum.us. Just look for the “Donate” link.

We ended our last episode with the dour spiritual condition of both the United States and Europe at the end of the 18th C.

I mentioned Dr. J Edwin Orr a couple of episodes back. He was the 20th C’s foremost expert on Revival and Spiritual renewal. While he could speak with eloquence on literally dozens of Revivals, one of his favorite subjects was what’s come to be known as the Second Great Awakening.

Before it began, there were many who worried if God did not intervene, Christianity might die out of Europe and the US.

Following Independence from England, many American intellectuals fell in love with France. But France was throwing off religious faith as fast as it could. The French Revolution made a mockery of the Church and Christianity. A well-known prostitute in Paris was crowned Goddess of Reason IN the Cathedral of Notre Dame. A majority of churches in France closed and the famous skeptic Voltaire claimed Christianity would be consigned to the dustbin of history in only 30 years. Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands were taken over by Rationalism. England was afflicted by a sophisticated Skepticism led by the philosopher David Hume. His attacks on faith are still used on campuses today.

French radicals contributed millions of francs to propagandize and seduce American students. In Christian colleges like Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, students welcomed the new French ideas, not because they promised justice, but because of they welcomed immorality. It was a time of great moral decline. Of a population of 5 million–300,000 were alcoholics. They buried 15,000 of them annually.

To give you an idea of just how prolific drinking was, President Washington had to call out troops to put down an armed revolt over alcohol in what’s come to be known as the Whiskey Rebellion. There was a plague of lawlessness with bank robberies a daily occurrence. Out-of-wedlock births and STDs sky-rocketed. Public profanity soared, cheating was epidemic. The turn toward immorality was so dramatic Congress appointed a special commission to investigate what had happened and how to correct it. The Commission discovered that in Kentucky, there’d been only one court of law held in five years. They simply could not administer justice on the frontier. It became so bad, a group of vigilantes formed and fought a pitched battle with the outlaws è and LOST!

A poll taken at Harvard found most students were atheists. At Princeton, a far more evangelical college; there were only two believers in the entire student body. All but five were members of the Filthy Speech Movement. Christians were so unpopular they had to meet in secret. Students burned down buildings and forced college presidents to resign. A mob of students attacked a Presbyterian church, breaking windows and burning the pulpit Bible. Students often entered churches during Communion to interrupt the service by spitting on the floor.

The largest and fastest-growing denomination had been Methodists. But they were now losing thousands each year. The second-largest were the Baptists. They described this time as their “most wintry season.” Presbyterians met in Philadelphia to express their dismay at the immorality of the nation. Lutherans and Episcopalians were so far gone they held talks to consider merging.

Samuel Provost, Bishop of NY had not confirmed anyone as a new member in so long, he quit and looked for other work. Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshal wrote to Bishop Madison of Virginia that the Church in the US was too far gone to ever recover. Charles Lee, a popular hero of the Revolutionary War loudly advocated pulling down all the churches claiming they were obstacles to progress.

The church historian Dr. Kenneth Scott Latourette summed it up by saying it looked as though Christianity was about to be ushered out of the affairs of man. But it wasn’t. On the contrary, a mighty outpouring of God’s Spirit was about to come.

In 1784, Pastor John Erskin of Edinburgh, Scotland published a plea for prayer by all Christians in Scotland. He sent a copy to Jonathan Edwards in America. Edwards replied in what became a book titled A Humble Attempt to Promote Explicit Agreement and Visible Union of God’s People in Extraordinary Prayer for the Revival of Religion and the Advancement of Christ’s Kingdom on Earth.

Erskin published both his book and Edwards’ reply as one-volume and sent it to Dr. John Rylands, a Baptist leader in Britain. Rylands read it, was profoundly moved, and pondered what to do with it.

He gave it to two men of prayer who determined to spread it among church leaders. They convinced dozens of Baptist churches to set aside the first Monday of each month to pray for a spiritual awakening. Other denominations found out about what the Baptists were doing and joined. Congregationalists, Evangelicals in the Churches of England and Scotland, and the Methodists all held monthly prayer meetings devoted to praying for revival. Within seven years Britain was covered with a network of prayer.

Then in 1791, the first evidence of an answer to their prayers began in the churches at Yorkshire. Mockers went to the monthly prayer meetings intending to disrupt them but went home converted. Some of these meetings were quiet prayer, others noisy.

Then in the city of Leeds, the Methodist Church there saw a thousand unbelievers brought to faith in just a few months. Soon all the churches were experiencing the same. What they saw was the renewal of believers and the conversion of the lost. And this winning of so many to Christ stunned both Baptists and Congregationalists. They didn’t believe in instantaneous conversion. They assumed it took three months of challenge, another three months of instruction to prove someone had been converted. That an alcoholic could attend a church meeting and go away converted and dramatically changed was hard to believe à Until they saw it happening in their own services. It revolutionized their understanding of conversion, changing it forever.

The revival strengthened Evangelicals in the Church of England like William Wilberforce who went on to lead the abolition movement in England.

The revival moved into Scotland. It swept Wales. By 1796 it had covered Norway.

One of the products of real revival is the new ministries it gives rise to. A pastor named Thomas Charles was moved by the story of Mary Jones, a serving girl who’d saved up her pennies to by a Bible. The nearest store was thirty miles away, so on her day off, she walked there, to find they were sold out. She returned home in tears. Pastor Charles was so moved he went to London and asked the publishers to print more Bibles. They refused saying the revival was a fad, a temporary emotionalism that would quickly pass and no one would want any Bibles then. So Charles formed the British and Foreign Bible Society, the first of all the Bible societies that would end up printing millions of Bibles that went all over the world.

The Second Great Awakening resulted in a massive missionary outreach as well as major social reforms. It led to the abolition of slavery, thousands of schools, and a host of organizations to help the poor and needy.

In the US and Canada, the first glimmers of revival began in 1792. It started in Boston where all but a couple of the churches had gone off into the error of Unitarianism. In Lenox, Mass. not a single young person had been received into the Church in 16 years. So a couple of churches agreed to hold special prayer for revival. They prayed for two years, then in 1794, a few pastors sent out a letter to every congregation in the US calling for a concert of prayer. They’d heard about what was happening in England and determined to do the same.

The Presbyterians adopted it in mass. Congregationalists, Baptists, and Moravians all took it up. Soon Christians across the nation were praying the first Monday of every month for spiritual awakening. Their prayers were desperate as they realized the urgency of the need. The momentum built over the next four years until 1798 when the Second Great Awakening began in earnest in the US.

One church in NYC began with 80 members. They prayed for revival and three years later had grown to 720. This was typical for most churches during the revival.

In the Eastern States, there was little to no emotional extravagance. But in the Western states of Kentucky and Ohio things were different. Remember the horrible conditions that existed on the Western frontier. People were brought under such conviction of sin they were often in an agony that once confessed and repented of, was replaced by unbound joy in salvation. Many would go from unrestrained weeping to dancing and celebration.

James McCready was the pastor of three small churches in Kentucky. McCready’s chief claim to fame was that he was so ugly he attracted attention. His voice was coarse and his style of preaching was far from elegant. In 1799 he said the ministry was “Weeping and mourning with the people of God.” But a year later, an outpouring of the Holy Spirit began in Kentucky.

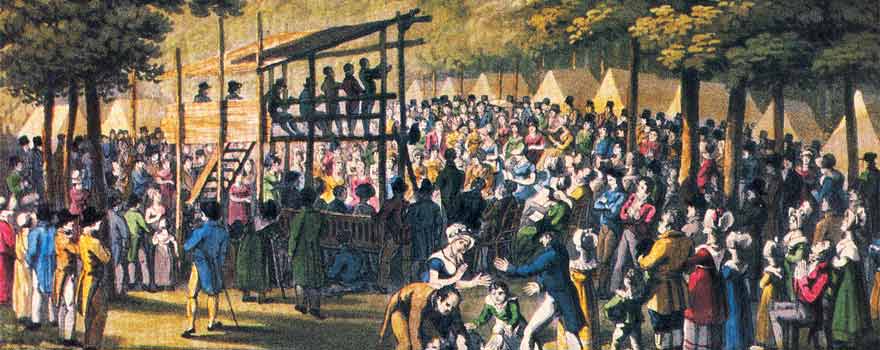

The churches of the frontier were small buildings inadequate to house all those who wanted to attend, so ministers like McCready rode to outdoor campsites where thousands gathered to hear the Word of God and take Communion.

At these camp meetings, as many as 20,000 would show up and stay for 3-4 days as one preacher after another preached.

The revival swept Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio. Dr. George Baxter, a Presbyterian minister from Philadelphia heard about what was happening and went to investigate. He said Kentucky was the most moral place he’d ever seen in his life. He heard not a word of profanity the entire time he was there. He said a sense of religious awe hovered over the entire countryside.

There was a great movement for the further evangelization of the Western frontier. Those who were converted traveled back East to attend college and get their degree in theology so they could return and continue the revival. So, revival broke out in those godless colleges of the East we talked about earlier. The Westerners returned home and started dozens of colleges in what today we call the Midwest. ¾’s of all Midwest colleges were the result of the Second Great Awakening.

The Revival swept the South and was as evident among the slaves as among the white population.

The War of 1812 interrupted the revival, but historians mostly agree that the Second Great Awakening marked the US as a thoroughly Christian nation.

As the Awakening began to lose steam, Charles Finney came on the scene with his revival efforts. Beginning in New York State in 1824, he conducted effective meetings in several Eastern cities. The greatest took place in Rochester, New York, in the fall and winter of 1830–31, when he reported a thousand conversions in a city of 10,000. The revival affected nearby towns as well, with over 1,500 making professions of faith. At the same time, there were about 100,000 conversions in other parts of the country from New England to the Southwest.

In 1835, Finney became president of Oberlin College in Ohio, where he continued to be an influential revivalist through personal campaigns and the wide distribution of his book Lectures on Revival. It was from the Oberlin school that the Holiness and Pentecostal churches emerged. Not only did Finney’s work make a great impact on America, he also made two trips to Europe, where he experienced extensive success.

Finney is credited with introducing something called the anxious bench in his meetings. This was a place for people who wanted to express a desire for conversion to sit and await someone leading them to faith by walking them through an understanding of the Gospel then praying with them. The modern-day altar call practiced in many Evangelical churches and meetings is the descendant of Finney’s anxious seat.

Fast-forward 50 years from the Second Great Awakening and it seemed the tide had gone out again. By the 1850s the country was thriving, largely because of the benefits brought by the Awakening. The Mid-West was being developed, the economy was booming. People made 18% interest on their investments. But as is so often the case, economic prosperity turned into a neglect of the Spirit. The pursuit of pleasure replaced the pursuit of God. The nation was politically divided over the issue of slavery. It wasn’t just States that were divided. Churches and denominations split over it.

Into this national argument that ended up tearing the country in two was added a dose of religious turmoil.

A veteran and farmer named William Miller rediscovered the doctrine of the 2nd Coming. For generations most of the Church considered Bible prophesy a closed book. Miller began teaching on the Return of Christ. But he made the mistake many have and said Christ would return in 1844. About a million people followed his views. When it didn’t happen, they were bitterly disillusioned because they’d sold their homes, businesses, and farms. Skeptics piled on the fanaticism of the Millerites and fired up a new round of mocking faith. Then, in 1857, things began to change. What that change was, we’ll take a look at it next time.

Actually I think I need this one as a transcript instead of 134. Is that possible?

Dawn, Look for an invitation to Google drive.